Lewis O. Beck, Jr. was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment nearly a decade ago, at 69. He continued working until recently, plays golf with three friends every Wednesday, and spends time with his miniature goldendoodle, named Bailey Irish Creme, a puppy his children pushed on him to help keep him engaged and alert. But his short-term memory is faltering, and his frustration is mounting. “Oh gosh,” says his wife, Mary Theresa Beck, known to everyone as Terri. “Appointments, appointments. I keep all our appointments.”

Early in 2022, Beck, who goes by Larry, enrolled in a study of an innovative experimental treatment for the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Instead of targeting the classic signature of the illness, brain plaque formed by the amyloid beta peptide and tangles of tau protein inside neurons, the treatment takes aim at a hallmark of aging itself, called cellular senescence.

Old age is the number one risk factor for Alzheimer’s, and scientists believe the root cause lies in the cellular and molecular changes we undergo as the years go by—the same changes driving many age-related conditions. One culprit may be what’s known as senescent cells. These no longer function as healthy cells yet they don’t die, which is why they’re nicknamed zombie cells. Instead, they release chemicals that trigger inflammation and damage healthy tissue.

Miranda Orr, an assistant professor of gerontology and geriatric medicine at Wake Forest University School of Medicine, devoted years to investigating why neurons die in a brain with Alzheimer’s. She concluded that the accumulation of senescent cells plays an important role, one largely overlooked in the decades-long effort to find a way to treat the disease.

Studies have shown that senolytics, a class of drugs that wipe out senescent cells while leaving healthy cells intact, help mice live longer and remain healthier. Some scientists believe these drugs have the potential to alleviate more than 40 age-related conditions. In a placebo-controlled study of 48 patients, Orr is testing her theory that senolytics can protect a brain in the early stages of Alzheimer’s from getting ravaged.

“What Miranda is doing is really cutting edge, and it’s opening up newer layers of research,” says C. Dirk Keene, a professor of neuropathology at the University of Washington School of Medicine. He believes her approach may point to novel strategies for preventing or treating one of the most agonizing, intractable diseases.

No downside to trying

The Becks live in Lexington, North Carolina. It’s a half-hour drive to the geriatric and clinical care center at Wake Forest medical school, where Larry is taking part in Orr’s study. They tell me they see no downside to signing up for an experimental treatment. “We felt like it couldn’t hurt,” Larry says. Nor do they expect miracles. “We’re kind of hoping that the different things that come along will help him stay right where he is,” Terri says.

Larry underwent an MRI, a PET scan, a spinal tap, blood work, and seemingly endless memory tests. Then he took five capsules on two consecutive days every two weeks, for three months.

The trial is testing the efficacy of two of the most widely studied senolytics: dasatinib, an FDA-approved medication for leukemia, and quercetin, a compound derived from plants that’s a popular supplement. Because both have long been in widespread use for other purposes, the Becks had no concerns about safety. But they understood from the start Larry might wind up getting placebos.

“We felt like if it didn’t help him in the beginning, it could help somebody later on,” Terri says. “It could help our children, you know, if something like this happened to them.”

Rethinking the roots of dementia

Alzheimer’s research has been dominated by the idea that eliminating brain plaque would solve the problem. It’s a long story of hope and heartbreak. Animal studies and small, early-phase clinical trials have shown various therapeutics eliminate amyloid or tamp down its production. But again and again, patients who received treatments that had appeared promising in the lab have gone on to suffer excruciating declines nonetheless. Meanwhile, the toll of the disease continues to climb. The World Health Organization estimates more than 55 million people across the globe live with Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia, with 10 million new cases diagnosed each year.

In a controversial decision in 2021, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved an amyloid-clearing drug, Aduhelm—the first Alzheimer’s medication to get the green light in 18 years—even though the agency’s panel of outside experts did not believe the evidence showed patients benefited.

In late 2022, the pharmaceutical companies Biogen and Eisai reported promising results from an international study of another anti-amyloid drug, lecanemab. The 18-month study of 1,795 people with early Alzheimer’s showed the drug significantly slowed, though did not halt, cognitive decline and cleared detectable plaques in the brain. About 12.5 percent of the patients had brain swelling and drug complications that have been common with experimental Alzheimer’s treatments.

By early 2023, however, the deaths of several people who were taking lecanemab raised concerns about its safety. The FDA approved the treatment in January 2023.

Similar drugs in the pipeline may prove to be safer than lecanemab and even more effective. But many scientists believe no single treatment, or approach, will obliterate Alzheimer’s, because the cause is likely so complex.

“It’s not just amyloid and tau,” says Howard Fillit, co-founder and chief scientific officer of the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, “These are pathological tombstones”—in other words, plaques and tangles are markers of devastating cellular and biochemical changes, perhaps the same ones that underlie other age-related diseases. Disappointment in anti-amyloid strategies has Alzheimer’s researchers like Orr looking for novel approaches by building on new insights into the biological processes that drive aging.

Scientists at Imperial College London, for example, are testing the drug sildenafil, better known as Viagra, for its ability to increase blood flow in the brain and alleviate blood-vessel damage in people with memory problems or mild Alzheimer’s. And a team at Norwegian University of Science and Technology plan to draw blood from healthy fitness buffs, ages 18 to 40, and inject their plasma into early Alzheimer’s patients, ages 50 to 75. The experiment was inspired by research showing that the blood of young mice can rejuvenate and extend the lives of their elders, and by human studies demonstrating that exercise changes blood composition in ways that enhance health.

The making of an Alzheimer’s researcher

Miranda Orr was inspired to study Alzheimer’s by her grandmother, a warm, fun-loving woman who had graduated high school as the class valedictorian and who loved strategic games, such as pinochle. Orr grew up in a small town in Montana, and when she was in high school her grandmother developed Alzheimer’s—her diminishing card skills were a sign of trouble.

“It was really hard to accept that there were no, absolutely no, treatments for her,” Orr recalls. She thought her grandmother could have received help if they lived in a city with state-of-the-art medical care, but over the next few years, Orr realized there was little to help patients anywhere.

“So as a 21-year-old, I decided I would cure Alzheimer’s,” she says. “I just thought, you know, maybe people haven’t thought of this yet. Reflecting back, I feel incredibly naïve. I realize a lot of people have been working on it, and it’s really, really challenging.”

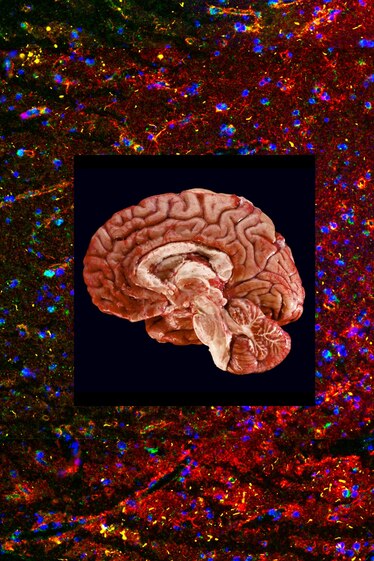

Orr, now in her early 40s, began her quest by using advanced imaging machines to study brain tissue from mice and Alzheimer’s patients, cell by cell. “We know the more tangles there are in the brain, the worse the dementia, and the more neurons that die,” she says. But those that die are not necessarily the ones with tangles, and experiments with mice showed that the tangles don’t kill the cells.

So what does? Complicating the mystery: People start accumulating tau in the brain decades before Alzheimer’s symptoms appear. What tips the scales to cell death and memory loss? As a postdoctoral researcher, Orr learned about cellular senescence and how it allows damaged cells to survive but at the cost of harming or killing neighboring cells. “And that was where things started to make sense,” she says.

She tested senolytics in mice genetically engineered to accumulate tau, and found the drugs reduced levels of that problematic protein, as well as inflammation and signs of senescence. The drugs also improved cerebral blood flow. She says she didn’t interpret the results to mean the disease got better, but that the treatment seemed to stop things from becoming worse. Findings from other researchers report that senolytics improved memory in mice with disease-causing accumulations of tau and beta amyloid.

Larry Beck was an early participant in Orr’s trial. He won’t find out whether he received the senolytics or sugar pills, or how the drug combination affects patients, until the study’s conclusion—Orr is aiming for the fall of 2024. Meanwhile, the accelerating pace of Alzheimer’s research gives the Becks hope.

“I feel very good that something is going to break through, whether it be at Wake Forest or someplace else.” Terri Beck says. And if any other scientist has a new drug to test, count Larry in, she adds. “We plan to do every study that will be offered to him.”

How healthy habits help

While the Becks wait for the next experimental treatment, I wondered what might be out there for the millions of us who show no signs of cognitive decline but worry about it. Perhaps they’ve watched a family member suffer from dementia—in my case, my father—and fear they may have a genetic risk, or they fret simply because they’re getting older. What preventive therapies are in the works?

Scientists in Northern Europe have demonstrated the protective power of a sweeping lifestyle intervention. It includes dietary guidance, exercise, computer-based memory training, social interaction, and close management of chronic conditions, such as diabetes and high blood pressure.

Some 40 percent of dementia cases are linked to these risk factors. Eliminating them would spare millions of people from hellish deterioration of brain function, says Miia Kivipelto, professor of clinical geriatrics at Karolinska Institute and creator of the intervention, called the Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability and known as FINGER. In its first large-scale trial, volunteers ages 60 to 77 who had these risk factors but no cognitive decline stayed on the intensive program for two years.

They showed such significant benefits in overall cognitive performance, memory, and executive function that roughly 45 countries are adopting and testing the model or plan to start soon.

And that’s a good reminder for anyone who hopes to live a long, healthy life and remain mentally sharp: Let’s not count on a breakthrough drug.

“I’ll be honest with you, the best bet is for us to take better care of ourselves during our lifetimes,” says C. Dirk Keene. “That’s what I think is going to make the biggest impact.”