For ancient seafarers, the ocean was a place of mists and uncertain landfalls. They described mysterious islands with godlike people, exotic creatures, and lost civilizations. Some islands magically appeared on the horizon, only to mysteriously disappear. Early maps became populated with islands floating in the oceans that, in the end, did not exist—as far as is known. But in between the mists of legend lie grains of truth. Maybe St. Brendan did set foot in North America before the Vikings. Perhaps a cataclysmic natural event did inspire the fall of Atlantis. Here’s what is known about six of the world’s most legendary isles.

(These fabled ‘ghost’ islands exist only in atlases.)

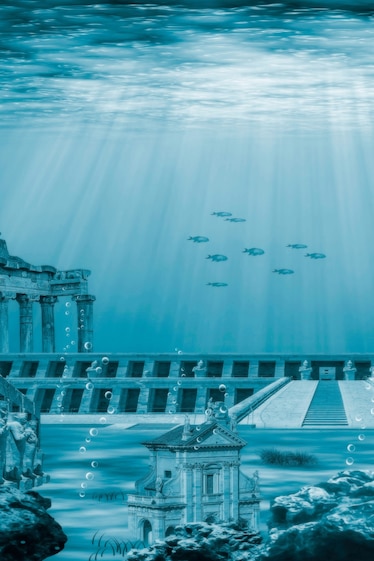

The advanced kingdom of Atlantis

Plato first wrote about the great island of Atlantis in his fourth-century b.c. dialogue, Critias. A godlike people famous for their “bodily beauty” and “moral excellence” dominated this mystical place, situated beyond the Pillars of Hercules (today, the Strait of Gibraltar). Atlantean kings ruled from a palace guarded by a wall of brass, a wall of tin, and a wall of copper.

My antediluvian baby

Later writers, including Sir Francis Bacon, William Blake, and American politician Ignatius Donnelly, kept Atlantis in the public’s consciousness, but was Atlantis really a place? Many historians and archaeologists believe that a historical catastrophe—an earthquake, tsunami, or vast flood— may have inspired the story. The most commonly invoked location is the Aegean Island of Santorini. Once a flourishing commercial center known as Thera, the city and its island were blown apart around 3,600 years ago in an enormous volcanic eruption, which may also have triggered a tsunami.

The lingering memory of this cataclysm may have shaped Plato’s tale. However, seekers after historical Atlantis have looked for proof in ruins in Spain, the Bahamas, and India, among other places, but to no avail. For now, explorers continue to look for Atlantis, or its inspiration, in sunken cities around the world.

(Read all about the legend of Atlantis.)

The end-of-the-world Thule

Greek explorer Pytheas first wrote about the mysterious island of Thule in his fourth-century B.C. work, On the Ocean. An intrepid traveler from Massalia (today’s Marseille, France), Phytheas visited and accurately described northwestern Europe. Thule, he wrote, was six days’ sail north of the British Isles, along the Arctic Circle. Scholar debate if Phytheas made landfall himself but wrote that it had neither land, nor sea, nor air, but a mixture of all three, with a texture of a jellyfish.

Geographers over the centuries linked Thule to a plausible variety of northern lands: Iceland, Greenland, Norway, or Nova Scotia (because Pytheas described its dramatic tides, which may have referred to the Bay of Fundy’s massive tidal range). Today, historians aren’t sure if Pytheas’s remote land was based on a real location or whether it is simply a stand-in for any place. Whatever the case, it shows up in the phrase “Ultima Thule”—any extremely remote place on Earth. And the name Thule lives on in Greenland with the Thule Air Force Base; in the Sandwich Islands, one of which is South Thule; and in the name of the 69th element, thulium, discovered by a Swedish chemist.

(These imaginary islands only existed on maps.)

Ireland’s phantom island of Hy-Brasil

Many ambitious sailors set out to discover the enchanted island of Hy-Brasil, which, according to Celtic myth, lay hidden in the mists and only became visible once every seven years. Fifteenth-century records from Bristol note that one Thomas Croft equipped two ships “and not with the intention of trading but of exploring and finding a certain island called the Isle of Brazil.” Italian explorer and navigator John Cabot apparently had Hy-Brasil on his agenda as he sailed toward North America in 1498. He disappeared with his ships, however, and the details of the journey are unknown.

It’s possible the mystery island was based on shoals to the west of Ireland, or that its occasional appearance was the result of a weather inversion, which can make distant objects appear to float above the horizon. The island itself gradually faded from the records.

(On the trail of Ireland’s legendary pirate queen.)

The monk’s island of St. Brendan

Brendan was an Irish monk, born in the late fifth century A.D. Known as Brendan the Navigator, his claim to fame is an epic journey to the Isle of the Blessed. The ninth-century Voyage of St. Brendan the Navigator describes how the aged cleric built a curragh, a traditional Irish vessel, and set out with other monks on an adventure that took him past pillars of crystal (possibly icebergs) and through rains of fiery stones (possibly volcanic eruptions near Iceland). The cliffs and landing place of another location visited match the coastline of the St. Kilda archipelago in Scotland’s Outer Hebrides. Eventually, Brendan landed on a lush island filled with fruits and precious stones, some of which he took home to Ireland.

St. Brendan’s Island appeared in various locations on Atlantic Ocean maps for centuries. Defenders of St. Brendan say that the land he found might actually have been North America, visited long before the first Vikings arrived.

(A long love affair with the Scottish Isles, in pictures.)

The isle of demons

In the 1500s, André Thevet, a French friar and writer, reported that sailors near the coast of Newfoundland would pass a particularly frightening but unseen island. They heard men’s confused and inarticulate voices and believed it was populated by demons and wild beasts.

The Isle of Demons shows up on maps as early as 1508. It would seem to be a sailor’s legend were it not for a very real French noblewoman, Marguerite de la Roque, who told of being marooned on the island by her uncle in 1542. (The young woman had offended him by entering into an affair with an officer on the ship.) Rescued and returned to France years later, she described being tormented by demons at night, as well as being menaced by bears “as white as an egg.” These presumed polar bears, being “vulnerable to mortal weapons,” she handily dispatched with the guns that her uncle had left with her.

Historians aren’t sure of the real identity of her island, though it may be Quirpon Island, Caribou Island, or Fichot or Funk Islands. The noisy demons? Possibly the cacophonous flocks of seabirds that nest on their shores.

The lost continent of Lemuria

The lost continent of Lemuria began as a legitimate scientific theory. Following the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species in 1859 but before the idea of plate tectonics emerged, researchers sought to understand why some animal species, such as the lemurs of Madagascar, appeared on widely separated lands. Perhaps, the theory went, a land bridge had once connected Africa and India. English zoologist Philip Sclater named this hypothetical land Lemuria, and scientists as distinguished as Alfred Russel Wallace endorsed the idea.

In the late 1800s, the cofounder of the spiritually questing Theosophical Society, Helena Blavatsky, hijacked this concept into her own mystical Atlantean/spiritualist narrative. According to Blavatsky, alien visitors had revealed to her that Lemuria was once the home of one of the “root races” of humankind: seven-foot, egg-laying hermaphrodites with psychic powers. Located in the South Pacific, Lemuria sank beneath the waves, but its inhabitants escaped to Central Asia. Other writers took up this concept, some claiming that the Lemurians were ancestors to Atlanteans.

Geology now explains the diverse locations of primate species. Nevertheless, Lemuria as an idea continues to thrive in comic books, movies, and video games.

To learn more, check out Mysteries of History. Available wherever books and magazines are sold.