Stealing from the rich to give to the poor, Robin Hood and his Merry Men are a permanent part of popular culture. Set in England during the reign of King Richard the Lionheart, the adventures of Robin Hood follow the noble thief as he woos the beautiful Maid Marian and thwarts the evil Sheriff of Nottingham. The story has been around for centuries, but its most familiar elements are also the most recent additions. (See also: Medieval cave tunnels revealed as never before.)

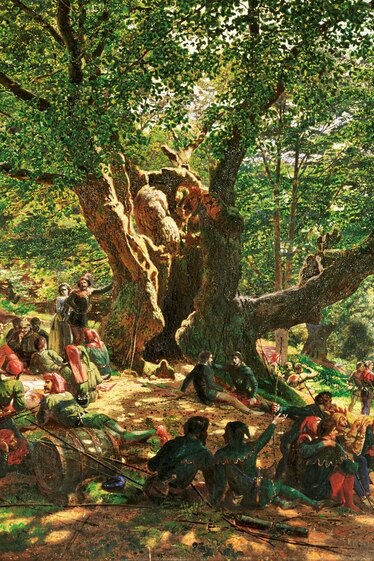

Like the roots of Sherwood Forest, the origins of the Robin Hood story extend deep into English history. His name can be found all over the English map: Robin Hood’s Cave and Robin Hood’s Stoop in Derbyshire; Robin Hood’s Well in Barnsdale Forest, Yorkshire; and Robin Hood’s Bay, also in Yorkshire. When the story is traced back to its 14th-century beginnings, the figure of Robin Hood changes with time. The earliest versions would be almost unrecognizable when compared to the green-clad, bow-wielding Robin Hood of today. As the centuries passed, the tale of Robin Hood evolved as England evolved. With each new iteration, the Robin Hood legend would absorb new characters, settings, and traits—evolving into the familiar legend of today. (See also: Traveling through unfettered Yorkshire.)

The first Robins

In 19th-century England numerous scholars embarked on a search for Robin Hood after the publication of Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe in 1820. Set in 1194, Scott’s novel takes place in England during the Crusades. One of the featured characters is Locksley, who is revealed to be Robin Hood, the “King of Outlaws, and Prince of good fellows.” Scott portrayed Robin as an honorable Englishman loyal to the absent King Richard; this popular characterization renewed modern interest in the figure of Robin Hood and the question of whether or not this “King of Outlaws” was based on a real person. (See also: Jesse James: Rise of an American outlaw.)

Historian and archivist Joseph Hunter discovered that many different Robin Hoods dotted the history of medieval England, often with variant spellings. One of the oldest references he found is in a 1226 court register from Yorkshire, England. It cites the expropriation of the property of one Robin Hood, described as a fugitive. In 1262, in southern England, there is a similar mention of a man called William Robehod in Berkshire. The previous year there had been a reference to “William, son of Robert le Fevere member of a band of outlaws”—believed to be the same person. In 1354, farther north in Northamptonshire, there is a record of an imprisoned man named “Robin Hood” who was awaiting trial. Because Hunter and other 19th-century historians discovered many different records attached to the name Robin Hood, most scholars came to agree that there was probably no single person in the historical record who inspired the popular stories. Instead, the moniker seems to have become a typical alias used by outlaws in various periods and locations across England.

A popular hero

When historical records failed to yield a definitive personage behind the noble outlaw, scholars than turned to the popular culture of medieval England: folklore, poetry, and ballads. These three formats all grew out of an oral tradition. Some theorize that they originally derived from troubadours’ songs that reported news and events. (See also: The hellish history of the devil: Satan in the Middle Ages.)

The first known reference in English verse to Robin Hood is found in The Vision of Piers Plowman, written by William Langland in the second part of the 14th century (shortly before Geoffrey Chaucer wrote The Canterbury Tales). In Langland’s work a poorly educated parson repents and confesses that he is ignorant of Latin:

I kan noght parfitly my Paternoster as the preest it syngeth,

But Ikan rymes of Robyn Hood...

The Middle English translates roughly to “Although I can’t recite the Lord’s Prayer (Paternoster), I do know the rhymes of Robin Hood.” Putting Robin Hood’s name in an uneducated character’s mouth demonstrates that the legend would have been well known to most commoners, regardless of whether they could read or write.

The Real Sherwood Forest

According to ballads, the setting of Robin Hood's adventures was not Sherwood Forest. It was Barnsdale Forest, which is in South Yorkshire, England. Over time, the legend became more closely associated with Sherwood, a forest lying to the north of the city of Nottingham and belonging to the king, whose sheriff was Robin’s great enemy. The laws governing the forest were tightened following the Norman conquest of England in 1066, and included extreme penalties for cutting down trees or hunting the king’s deer. The locals were being shut out of prime hunting ground, which led to the unpopularity of the laws. Because the lands were protected from clear-cutting, the woods remained a wild place, making it the perfect setting where outlaws could hide and adventures could be spun.

By the 15th century the Robin Hood legend took on its first trappings of rebellion against the ruling class. One of the oldest known written ballads about the forest outlaw, “Robin Hood and the Monk,” dates to around this time. It is the only early ballad to be set in Sherwood Forest near Nottingham, and it features Little John, one of the best-known members of the band of Merry Men. In the tale Robin Hood ignores the advice of Little John and leaves the safety of the forest. He travels to Nottingham to attend Mass and pray to the Virgin Mary. At church Robin is recognized by a monk who turns him over to the sheriff. The monk then sets off to tell the king of the outlaw’s capture, but before he can arrive, Little John and Much, another of Robin’s men, overtake the monk on the road and murder him and his servant.

Posing as the monk and his page, Robin’s men deceive the king. They deliver the news of Robin’s capture to him and are rewarded with money and titles. They return to Nottingham and free Robin from prison. The sheriff is humiliated but survives the story, while Robin, Little John, and Much return to the forest with the forgiveness of the king. In this story the monk—not the sheriff or the king—is the true villain. The monk is a corrupt figure who violates the sanctity of the church by betraying Robin’s presence to the sheriff.

This version of the legend visits extreme violence on the villain, delivered by Little John and Much. The killing of the monk is justified because of his corruption, while the death of the monk’s page, to avoid leaving a witness, is also accepted, despite the page’s innocence. Later versions of Robin Hood stories would move away from these deaths that appear as collateral damage, but medieval audiences did not seem overly troubled by them.

Medieval crime and punishment often centered around brutality and violence. Kings, lords, and their representatives used it often to punish rebellious peasants. Bodies hanging from the gallows or displayed as a warning at crossroads were familiar sights during this time. These early Robin Hood ballads begin to show a turning of the tables, in which the lower classes are able to punish the upper classes through trickery and violence.

In the 15th century more ballads about Robin Hood spread across England. One of the longest, A Gest of Robyn Hode, originates during this time. In this work is one of the first iterations of Robin Hood’s edict of stealing from the rich to give to the poor. In the poem Robin says, “If he be a pore man, Of my good he shall have some.”

In these tales Robin belonged to the lower classes and was considered a yeoman. The medieval English ballads use this term to describe a status higher than a peasant but lower than a knight. In its original sense “yeoman” meant a young male servant, applied to servants of standing within a noble house. In the Gest Robin is depicted as a Yeoman of the King who, despite his privileged position, misses the forest and so chooses to abandon the court.

Robin Hood takes on a role as an administrator of justice for the underclass in the Gest. When Little John consults his leader for guidance on whom to beat, rob, and kill, Robin Hood provides him with a code divided along the lines of rich and poor. No peasants, yeomen, and virtuous squires were to be harmed. On the other hand, the Merry Men were allowed to “beat and bind” bishops, archbishops, and, above all, the loathed Sheriff of Nottingham. In the Gest the type of villains has widened to include more figures at odds with the lower classes.

The Robin Hood legend also takes a bloodier turn than in previous versions as vengeance is delivered to villains. In the Gest Robin shoots the sheriff with an arrow and then slits his throat with a sword. In a 15th-century manuscript of Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne, Robin is not content with just killing his opponent, Guy. He also mutilates the corpse with a knife, a deed he carries out with considerable relish.

Scholars sometimes explain these recurring themes of duping and punishing corrupt people in power as reflecting a struggle between dispossessed Saxons of the countryside and the powerful Norman rulers in the cities. In the centuries when the Robin Hood legend was taking shape, the English government was beset by a number of crises that upended the social order. A civil war in the 12th century, later known as the Anarchy, led to a catastrophic breakdown in law and order. In the 14th century the Black Death and Hundred Years’ War with France placed a huge burden on the lower classes, who, in 1381, launched the Peasants’ Revolt.

Another Adversary

The Sheriff of Nottingham is not Robin Hood's only enemy. Sir Guy of Gisborne plays the part of the villain in many stories. Originating around the 15th century, Robin Hood and Guy de Gisborne describes an encounter in the forest of Barnsdale. Not recognizing Robin, Sir Guy asks him for directions through the wood and tells him he is hunting for the outlaw Robin Hood. Robin suggests that they have an archery contest and then bests Sir Guy before revealing his true identity to him. The two men brandish knives and fight. Robin kills his adversary, sticks his severed head on the end of his bow, and disfigures the face with his knife. ”There you stay, good Sir Guy,” he says, and then he disguises the dead man’s body in his own clothes of green.

A class act

In the 16th century Robin Hood lost some of his dangerous edge as he and his men were absorbed into celebrations of May Day. Every spring, the English would herald in the spring with a festival that often featured athletic contests as well as electing the kings and queens of May. As part of the fun, participants would dress up in costume as Robin Hood and his men to attend the revels and the games.

It is during this period that Robin Hood also became fashionable among the royalty and even associated with nobility. One story from 1510 claims that Henry VIII of England, then barely 18, dressed up like Robin Hood and burst into the bedchamber of his new wife, Catherine of Aragon. There, accompanied by his noblemen, he entertained the queen and ladies-in-waiting with his exuberant dancing and high jinks. In 1516 King Henry VIII and Queen Catherine took part in May Day festivities. Two hundred of the king’s men dressed in green and one dressed as Robin Hood led the monarchs to a feast.

Several more characters begin to appear in the Robin Hood stories at this point. One is Maid Marian, and the other is Friar Tuck. The two enter into the legend at around the same time. Like Robin Hood, these two were also popular figures at the May games, and they begin appearing in literary works as well.

One of Friar Tuck’s earliest appearances is in the play Robyn Hod and the Sheryff off Notyngham, which dates to approximately the late 15th century. His popularity grew in the coming years, and he appeared more frequently in later works, such as Robin Hood and the Friar from the 1560s. This work features an episode where the monk bests Robin Hood and tosses him in a stream.

In the Elizabethan era Robin Hood became a popular presence in plays staged for the upper classes. Several playwrights, such as William Shakespeare, featured him in their works. Most notable was Anthony Munday, who wrote two plays centered around Robin Hood. Munday reinvents the outlaw as an aristocrat: Robert, Earl of Huntington, whose uncle disinherits him. Robert flees to the forest where he becomes Robin Hood. There he meets Maid Marian, and the two fall in love. No longer was Robin Hood a yeoman; he had been gentrified for new audiences.

Munday sets his works during the reign of Richard I, the Lionheart. The king has left England to fight in the Holy Land, and his younger brother John rules in his stead. Although Munday’s Robin Hood plays are regarded by modern critics as poorly constructed and a bit dull (most of the action had to be written out to avoid censorship), their influence has been considerable. Setting the tale during King Richard I’s reign became popular with other authors when they interpreted the legend for themselves. Munday’s decision to make Robin Hood a nobleman also recurred in later tellings.

For the ages

Drawing on the medieval foundations, authors would continue to reinvent Robin Hood for their own times over the centuries. Walter Scott repackaged Robin Hood for Ivanhoe in the 19th century, while Howard Pyle most famously re-created the legend for a children’s book, The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood of Great Renown in Nottinghamshire, in 1883. Pyle’s work gained a new audience for Robin Hood in the United States, which seemed to hunger for more tales of the Prince of Thieves in years to come. In 1917 author Paul Creswick teamed up with notable illustrator N. C. Wyeth to create a colorful Robin Hood, one of the most visually striking renditions of the tale.

In the early 20th century Robin Hood migrated from the page to the cinema, and the tale was reinvented and retold time and again with stars like Douglas Fairbanks, Errol Flynn, Sean Connery, and Daffy Duck all taking their turn in the lead role. In each version, glimmers of the original ballads and poems remain visible as each new version adds more to the legend of the Prince of Thieves.