In February, fine red dust borne by winds from the far-off Sahara coats everything in Foumban, a town of about 100,000 in Cameroon. In a month the spring rains will start, but for now every day feels the same—hazy sun, dry heat, and on the main road through town, a cacophony of honking horns and buzzing motorcycles.

For a few decades this part of Africa was a colony of Germany, whose brief but brutal rule lasted from 1884 until 1916. Like other colonial powers, Germany established ethnological collections to conserve, study, and display cultural artifacts from its new colonies. Though collecting is an impulse with deep roots in human history, museums as we know them are mostly a 19th-century invention, designed to share the fruits of European exploration and conquest.

Colonialism turned collecting into something of a mania. Just as colonial powers didn’t send explorers to map new corners of the globe for pure love of knowledge, objects didn’t simply fall into museums. Anthropologists, missionaries, merchants, and military officers worked with museums to bring wonders and wealth back to Europe. Curators even sent wish lists along with armed colonial expeditions.

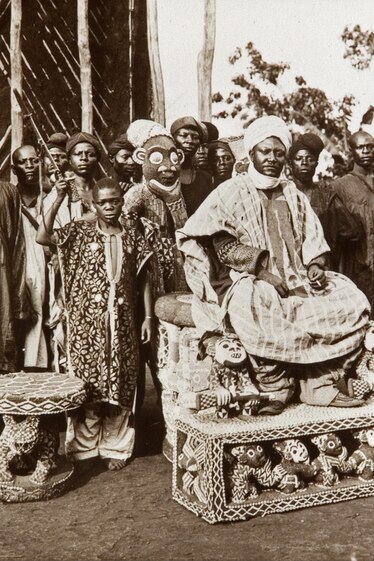

In 1907, German officials gave a message to Sultan Ibrahim Njoya, ruler of Cameroon’s Bamum people. Perhaps, they suggested, a gift to Kaiser Wilhelm II for his upcoming 50th birthday would be a welcome gesture—specifically a precise replica of Njoya’s remarkable, elaborately beaded throne. An inheritance from the king’s father, the throne was known as the Mandu Yenu, after the pair of protective figures that adorned its back.

Njoya had turned down many German offers to buy or trade for the throne, but in this case he agreed. If he wrote down why, those records are lost. Maybe it was a gesture of gratitude to thank colonial officials for sending troops to help him fight and defeat his neighbors. Or maybe Njoya was worried what would happen to his kingdom if he refused. One thing is certain: He asked his carvers and beadworkers to make a copy of the Mandu Yenu. But when it became clear that the copy wouldn’t be ready in time for Wilhelm’s birthday, Njoya was persuaded to hand over the original instead. It has been in the collection of Berlin’s Ethnological Museum ever since.

Njoya’s great-grandson, Nabil Njoya, became ruler of the Bamum in 2021, following the death of his father. When I meet him in front of the royal palace in Foumban, the 28-year-old king pulls out his mobile phone and shows me photos of a college kid in a New Jersey Nets hat—selfies he took during the five years he attended college in Queens, New York.

In modern Cameroon, Nabil’s kingship is a traditional title with limited legal authority, but it carries respect and symbolic power. And according to Bamum custom, the power of each king is passed via the thrones they build for their successors. As long as the Mandu Yenu remains in Berlin, “there’s a break in the chain.”

Seated on the throne his father had built for him, Nabil says he doesn’t blame Germans for things their ancestors did more than a century ago. He just wants his great-grandfather’s throne back. “None of us here were present at that time—none of us,” he says in a French accent with a bit of Queens thrown in. “But I think that we are obliged to solve the problem.”

To house the Mandu Yenu throne and other Bamum artifacts, Nabil’s father built an eye-catching museum on the palace grounds. Shaped like a double-headed snake, it’s topped with a realistic, hairy-legged spider—traditional symbols of power, vigilance, and hard work.

Nabil hopes bringing the Mandu Yenu home will be part of his legacy. “I have a picture in my mind,” he says. “I see me and that throne. I see a lot of Bamum people all around me. And I’m seeing, standing next to me, the director of the Berlin museum shaking hands with me, and both of us saying, ‘We did it! We did it—not for us, but for our children.’ ”

Not many people in Germany have heard of the Mandu Yenu throne. Even fewer could locate Foumban on a map. But while objects from other places—Benin, Egypt, Greece, Nigeria—have dominated headlines in recent years, the finely beaded wooden throne captures the messy, confusing, uncertain, and ultimately hopeful future of an unprecedented global moment.

Over the past few decades, a new generation of museum curators and directors—often prodded by activists and political leaders—have been digging deeper into how objects in their museums came to be there. Increasingly, they’re going a step further. In a process known as repatriation or restitution, they are pulling art, ritual objects, and human remains out of display cases and storage rooms and giving them back to the communities where they originated.

Last year alone, Germany transferred ownership of hundreds of objects to Nigeria’s national museum commission, France handed 26 artifacts back to Benin, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York cut a deal to transfer ownership of dozens of sculptures to Greece.

“Around 1900 you had competition between European nations to have the biggest ethnological collections,” says Bénédicte Savoy, a professor of art history at the Technical University of Berlin. “Now I think we have a competition to be the first to give the things back.”

Many curators hope the shift will be the beginning of a new era of cooperation between museums and the communities and countries their collections originally came from. Critics, meanwhile, worry that the returns may spark a chain reaction that will dismantle “universal” museums whose international collections offer unique insights into how the world is interconnected.

If the past five years represent a revolution in how museums view their collections, perhaps it’s appropriate that the spark was struck in France, where so many revolutions have begun. In November 2017, French president Emmanuel Macron traveled to Ouagadougou, the capital of Burkina Faso, a former French colony in West Africa. In front of an auditorium filled with students, he acknowledged the “crimes” of France’s colonial period. Then the speech took an unexpected turn.

“I cannot accept that a large share of several African countries’ cultural heritage be kept in France,” Macron told the audience. “There are historical explanations for it, but there is no valid, lasting, and unconditional justification.” Within five years, he said, “I want the conditions to exist for temporary or permanent returns of African heritage to Africa.”

Watching the speech at her gallery in Benin, another former French colony, Marie-Cécile Zinsou, who runs a foundation focused on contemporary African art, was stunned. “No one knew it was coming,” she says. “It was like a thunderstorm.” Just a year before, a request from the president of Benin for objects taken by French soldiers in the 1890s had been dismissed outright. “France had always said no,” adds Zinsou.

Soon afterward, Macron asked Savoy and Senegalese scholar Felwine Sarr to prepare a report on France’s colonial collections. In an 89-page document published by France’s culture ministry, the two researchers called for France to return objects taken by its military during the colonial era, along with pieces taken by the armies of other countries and held in French museums. They also pushed for the return of artifacts acquired on “scientific” expeditions sent to Africa in the early part of the 20th century to collect items, often at gunpoint, for French museums.

From Ghana to Greece, former colonies had been asking for their artifacts to be returned, some for half a century or more. Finally, governments, museums, and the media were starting to listen.

On a sweltering Monday in July, I went to meet the man whose museum is perhaps most affected by Macron’s promise. The Quai Branly Museum, a short walk from the Eiffel Tower in Paris, houses France’s largest ethnological collection. Dating back 500 years, to the time of cabinets of curiosities, the collection includes everything from Polynesian wood carvings to decorated human skulls from the highlands of Papua New Guinea. In charge of it all is Emmanuel Kasarhérou. His appointment in 2020 was a strong signal that things in the museum world were shifting. A native of New Caledonia, an archipelago in the Pacific Ocean 10,500 miles from Paris, he’s a member of the Kanak people and one of the few Indigenous museum directors in all of France.

In 2021 Kasarhérou presided over the return of artworks taken by French soldiers in 1892 after the sack of Dahomey, a West African kingdom in what is now the country of Benin. The items—including two thrones, the doors of the palace, and other symbols of royal power—had been a centerpiece of the Quai Branly’s collections since its opening in 2006.

Not long after Macron’s speech, Benin’s president, Patrice Talon, requested the objects again. French legislators passed a narrow law authorizing the return of those specific items in 2020. In February 2022, the objects were unveiled at the presidential palace in Cotonou. “The patrimony of Benin has returned,” Talon told a crowd of reporters at the opening.

For hours, Benin’s elite mingled among the returned artifacts and an exhibit of work by contemporary Beninese artists. The high-ceilinged halls were crowded with foreign ambassadors, barefoot vodou priestesses, and army officers in black-and-gold dress uniforms. Dahomey royalty in red-coral necklaces walked slowly past ancestral treasures in glass cases.

As night fell, the dignitaries trickled out and the staff wandered in. Security guards and chefs in tall hats reverently posed for selfies with the historic objects. When I finally slipped out a side door into the warm, humid night, they were still there. Over the next four months, nearly 200,000 people visited the exhibitions, sometimes waiting in line for hours for a chance to see the returned artifacts. The great majority of visitors were from Benin—a rebuke to the idea that Africans aren’t interested in their own history or in museums.

Savoy, too, was in Cotonou for the ceremony, her eyes twinkling as she surveyed the crowded galleries. Macron’s 2017 promise was on track, and museums were playing a new role—as places to talk about the future, not just capture the past. “Before all these restitutions began, you had a lot of people saying, If you give one thing back, our museums will be empty,” she says. “I don’t think that’s going to happen.”

Not all museums see it that way. The British Museum in London has become a global symbol for its refusal to return objects. In the past, museum officials have argued that the world needs universal or encyclopedic museums that cut across the artificial divides of modern borders and bring together art and artifacts from different cultures, time periods, and places. It’s an idea that originated in the Enlightenment, the flourishing of science and philosophy that swept Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries. “Where else on our planet can we bring together under one roof the fruits of two million years of human endeavor?” the head of the museum’s board of trustees, George Osborne, said in a speech last year. “We want this to be the museum of our common humanity.”

It’s easy to warm to the idea, if you’re lucky enough to be in London with an afternoon to spend at the British Museum. A few months before Osborne’s speech, I strolled through the museum’s vast main hall and past the Rosetta stone. Carved in 196 B.C., the famed stela was discovered near Alexandria, Egypt, by Napoleon’s troops in 1799 and brought to London in 1802 after the British defeated the French. Just beyond it are Assyrian reliefs sculpted almost 3,000 years ago, then a Roman copy of a Greek statue of Aphrodite purchased by the British king from an Italian duke in the 1620s. Each object’s biography is a collision of cultures and influences, a minicourse in world history.

A few steps farther is a gallery with marble reliefs marching the length of the cathedral-like space. These exquisite sculptures, carved 2,500 years ago, once adorned the Parthenon in Athens. Six million people visit the British Museum each year, and it’s a safe bet most of them have at least heard of demands that the marbles go back to Greece—a debate that has raged on and off since the sculptures were brought to London more than 200 years ago. In December, rumors that Osborne was in secret talks with Greece over the stones made headlines, even as museum officials stayed silent.

Hoping to better understand the museum’s position on the Parthenon marbles and other controversial artifacts, I pull out my phone and download a digital tour titled “Collecting and Empire Trail.” It’s a letdown. The tour points me to a Chinese soup plate, a betel nut cutter from Sri Lanka, and other objects acquired during the glory days of the British Empire. But the subjects of recent heated claims—including the Rosetta stone, the Parthenon sculptures, the Benin Bronzes, and the “Hoa Hakananai‘a,” a towering stone moai spirited away from Easter Island by British sailors in 1868—are conspicuously absent.

Before visiting London last summer, I tried for months to get the museum to agree to an on-the-record interview, to no avail. As museums elsewhere have grappled with the restitution question, the British Museum seems to have gone into hiding.

Even the museum’s longtime defenders seem flummoxed. After wandering the museum’s sprawling galleries, I meet author Tiffany Jenkins for tea. In 2016 Jenkins wrote a defense of the British Museum entitled Keeping Their Marbles, arguing that modern museums should focus on telling the stories of ancient objects and the people who made them, and steer clear of political posturing.

To my surprise, Jenkins admits that in the years since her book was published, the debate has shifted dramatically—and left the British Museum behind. Museum staff, she points out, rarely make the case for encyclopedic museums anymore. Instead, they’ve retreated to technicalities, like agreements signed in the 1800s with the Ottoman Empire, which then controlled Athens, to remove marbles from the Acropolis. Or the fact that many objects were taken from Africa and Asia before Britain signed a treaty that banned looting, making their acquisition legal, if not ethical. Or a 1963 act of Parliament that prevents the museum from removing items from its collection, cited by the British prime minister in December in an effort to quash rumors that the secret talks between Osborne and Greek officials over the Parthenon marbles signaled an imminent return. “Just pointing to the paperwork isn’t an answer,” Jenkins says. “If that’s their argument, they’ll lose.”

Perhaps there's a middle ground. Hermann Parzinger is president of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, or SPK, an umbrella organization that oversees more than a dozen Berlin museums. They include two museums in the controversial Humboldt Forum, a new complex in the middle of town. Its Ethnological Museum houses hundreds of thousands of artifacts, most of which were accumulated during Germany’s colonial heyday in the late 19th century.

For decades, Parzinger and his predecessors made headlines for pushing back against repatriation requests from Egypt, Turkey, and former German colonies in Africa. But in a sign of how quickly the debate has shifted, the SPK has moved to return numerous objects since 2018, including a goddess figurine to Cameroon, ritual and cultural objects to Namibia, the remains of Maori people to New Zealand, and the remains and funerary items of Indigenous Hawaiians and Alaska Natives to the United States.

Last year, the SPK was part of a blockbuster return of Benin Bronzes to Nigeria. (The “bronzes” include items of ivory, wood, and brass, but the name took.) In 1897, a heavily armed British expedition invaded the Edo empire, overthrew its hereditary king, or oba, and plundered his palace in Benin City, the heart of the Kingdom of Benin. Grainy photographs of the aftermath show British soldiers, their faces and uniforms smudged and dirty, grinning amid stacks of ivory and metal statuary. Officers captioned some of the photos “LOOT.” Curators from German ethnological museums bought hundreds of bronzes at auctions staged to cover the costs of the raid.

Today more than 5,000 objects taken in the 1897 raid are held in museums around the world rather than at the National Museum in Benin City. “What the British took was a treasure trove of objects that had been in the palace for centuries,” says Theophilus Umogbai, the museum’s former director. “They created a vacuum in our history, a gap in our library.”

The Benin raid’s well-documented circumstances, along with decades of persistent pressure from Edo royalty and Nigerian officials, made the bronzes a prominent test case for repatriation. The combination of a strong moral argument and public and political pressure seems to be shifting the debate.

“We do not want looted objects in our collections,” Parzinger tells me firmly. Even a handful of museums in the United Kingdom have moved to return pieces, and donations from the U.K., Germany, and elsewhere are helping fund a new museum in Benin City designed by Ghanaian British architect David Adjaye.

In July, German government representatives issued a bilateral declaration that legal ownership of Benin Bronzes in museums across the country—more than 1,000 objects, including 500 from the SPK—should be transferred to Nigeria. At a signing ceremony, Nigeria’s culture minister called it “the largest known repatriation of artifacts anywhere in the world.”

The moment was powerfully symbolic—and, Parzinger says, a win-win. Many of the objects will stay in Germany on long-term loan for the next 10 years, and others will remain until Nigeria builds new museums with German help. After that, Nigerian officials will lend artifacts to Germany on a rotating basis.

“I want to show the art of Benin in my museum,” Parzinger says. “But whether these objects are loans or property of my museum is in the end not that important.”

In August the SPK became the first German institution to officially sign over its bronzes. So what hope is there for more complex cases, such as the world-famous bust of the ancient Egyptian queen Nefertiti? The exquisite sculpture was excavated by German researchers in 1912 and sent to Berlin, where it has remained ever since. German officials argue that it was legally acquired at the time and that repatriation requests haven’t come through proper channels.

Parzinger says each request must be evaluated on its own merits, with input from local communities and national governments and research into the circumstances of individual acquisitions. “There’s been museum bashing and harsh dialogue that painted a picture that everything is stolen and illegal, but one has to look at the gray zones,” Parzinger says. “A museum is not a space where you just go in and take what you want off the shelves.”

What about Ibrahim Njoya’s throne? I ask. No Bamum ruler has ever made a formal request for the throne’s return, nor has the government of Cameroon. But what if they did?

Parzinger frowns. Njoya, he points out, benefited from his alliance with German colonizers. The Bamum king grew rich from trade with German merchants and defeated local rivals with the help of German weapons and military assistance. Seen from Parzinger’s perspective, the idea that the throne was a gift to thank Germany for its help isn’t so far-fetched.

“When you see how well they played together, to see Njoya now completely as a victim? That, for me, is a little bit difficult,” he says. He pauses, considering. “I’m sure solutions can be found. Before the throne left Bamum, they produced a copy. Maybe there can be an exchange?”

To call all this a huge shift is an understatement. Just 20 years ago, Parzinger’s predecessor dismissed the idea of even lending some of

the museum’s Benin collection to Nigeria. Today museum curators are meeting their counterparts in former colonies for eye-to-eye discussions, sometimes for the first time. “Maybe it’s the end of the 19th-century museum,” Savoy says, sounding entirely unbothered by the prospect, “and the beginning of something else.”

For a sense of what that might look like, I head to Suitland, Maryland, a Washington, D.C., suburb where the Smithsonian Institution keeps most of its 157 million artifacts in a multi-acre storage and research complex. The collection includes millions of items gathered from Native American tribes over the past 200 years. The National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) support center consists of five pods, each the size of a football field and three stories tall. In one section, airtight cabinets house objects from hundreds of U.S. tribes.

The Smithsonian has long welcomed scholars who come to use its collections for research, but over the past 30 years the NMNH support center has created spaces for other visitors. Nowadays tribal representatives regularly come to the facility to see items made by their ancestors and to work with curators. A conference room doubles as a ceremonial space, complete with a cabinet stocked with dried sage and tobacco for tribe members to burn in purification ceremonies before or after handling sacred objects.

Thirty years ago such scenes would have been hard to imagine. For centuries archaeologists, ethnographers, and museum curators enthusiastically collected Native American artifacts and human remains. Burials were excavated without the consent of descendants.

“When these items were acquired, collectors weren’t thinking of Indigenous peoples as human beings,” says Jacquetta Swift, the repatriation manager for the National Museum of the American Indian. “People were resources, and human remains were to be preserved alongside pots,” adds Swift, who’s from the Comanche and Fort Sill Apache tribes.

In the 1970s and ’80s, Native American activists successfully lobbied for laws that would require museums to hand over the bones of their ancestors, along with sacred objects. Many museums pushed back, hard. The concerns raised back then sound familiar to anyone following the debate in Europe today.

Anthropologists and archaeologists worried that relinquishing collections of human remains would be an irrecoverable loss to science, making it impossible to study the country’s prehistoric past. Others charged that tribes would be unable to properly care for artifacts or would damage them in traditional ceremonies. And others suggested tribes would use the law to empty out museums for profit.

“There was a considerable amount of hostility between museums and communities,” says Kevin Gover, the Smithsonian’s undersecretary for museums and culture and a citizen of the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma. “There was a lot of resistance to the idea of repatriation in general.”

In 1989 Congress passed the National Museum of the American Indian Act, followed in 1990 by the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, known as NAGPRA. The laws made the Smithsonian and other U.S. museums responsible for developing a collaborative repatriation process with tribes, recognizing rights that previously didn’t exist.

The National Museum of Natural History set up a repatriation office in 1991. Since then it has returned more than 224,000 items to 200 different tribes, along with the remains of 6,492 people. The process has been repeated at smaller museums around the nation.

While thousands of objects have been returned, some have stayed. Eric Hollinger, the tribal liaison in NMNH’s repatriation office, stops halfway down one of 46 rows of cabinets and swings open a door, releasing the pungent smell of wood and old leather. Inside there are blankets, beaded cradle covers, and buffalo calf robes—offerings left for a Cheyenne child who died in 1868. Not long after, U.S. Army soldiers tracking the tribe found their abandoned encampment and the burial. They boxed up the offerings and the child’s body and sent everything to the Army Medical Museum. The Smithsonian eventually acquired the collection, but at some point the child’s remains were lost.

In 1996 representatives of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma worked out an agreement to allow the objects to remain at the NMNH “for research and education to be conducted by scholars and the Cheyenne people.” Photographing or displaying them requires written permission from the tribe. It’s an example of shared stewardship that gives both sides responsibilities for an object’s future.

“Although these items were not repatriated, the tribe agreed to share their care, and they never left the museum,” Hollinger says. “People think it’s about removing the objects, but really repatriation is about transfer of control.”

Some cabinets have ventilation holes because tribes see the objects inside as living spirits that need to breathe. In others, objects are oriented in a certain direction in keeping with tribal beliefs.

The museum still regularly gets return inquiries. Before agreeing, researchers talk to tribal representatives and comb through journals and diaries to discover all they can about how the object was acquired. Whether or not tribes ultimately make a claim, both sides usually find out something new about the object along the way. The consequences of NAGPRA were not dire, Gover says. “We learned a lot about those cultures we didn’t know.”

That’s not to say the U.S. experience has been entirely successful. The bones of more than 100,000 individuals still languish in boxes and locked storerooms across the country, often because tribes haven’t been able to prove a direct relationship based on records provided by museums—or because curators have dragged their feet. “We need to do better,” Gover says. “This needs to be a priority for museums that hold Native American remains.”

While ethnographic museums were once static storehouses, today’s museums are increasingly trying to create exhibits with the participation of communities, asking them how they want to be represented and what objects are significant to them. Using laser scanners, Hollinger and a team of specialists worked with the Tlingit people of Alaska to create 3D replicas of a damaged ceremonial sculpin hat. One replica was kept for the museum to exhibit alongside the original, while the other was consecrated by the Tlingit as a living ceremonial object for the community to use.

The National Museum of the American Indian encourages curators to add contemporary pieces made by Native artists to its collections. In its exhibits on the National Mall in downtown Washington, D.C., the museum displays 19th-century buffalo robes, wampum belts, and Lakota eagle-feather headdresses. But it also displays a hard hat painted by a Mohawk construction worker, as well as Christian Louboutin stiletto heels covered in traditional glass beadwork by Jamie Okuma, a Native artist from California.

“The ethnographic museum of the past is making its way to the exit,” Gover says. “It tried to freeze these cultures in time, and no culture stops. We want to make the point that these communities are here; they’re present and alive and vibrant.”

Nowhere is that shift clearer for me than in Benin City, Nigeria, in an outdoor studio littered with broken clay molds and gleaming brass sculptures. Under the shade of a corrugated metal roof, unfinished plaques await polishing with an angle grinder. The smell of honey mingles with the tang of smoke and sweat as beeswax models soften in the 95-degree heat.

Presiding over it all is Phil Omodamwen, a sixth-generation bronze caster. His forefathers were part of a guild that created bronze plaques and sculptures for the Edo oba. As a pair of assistants stoke a white-hot bonfire, Omodamwen explains that the techniques he uses today build on those used for the past 500 years. He recycles scrap metal to cast elaborate bronze and brass sculptures. Repurposed refrigerator and air conditioner compressors serve as crucibles for the bubbling, green-gold, molten metal.

When I visited last February, the rumored return of bronzes from Germany dominated the talk on Igun Street, where bronze casters sell their work. Many hoped repatriation represented a future for an ancient tradition. In the shade of a thick-trunked palm tree, Omodamwen tells me he may be the last bronze caster in his family. One of his sons is an accountant, the other a cybersecurity consultant. “I don’t think they will continue after me,” Omodamwen says, with a mix of pride and sadness. “I’m worried that in the next 20 years, bronze art will go into extinction.”

In a derelict office building not far from Igun Street, I catch a glimpse of a different future as 28-year-old Kelly Omodamwen—Phil’s cousin—tells me he grew up watching his father and uncles cast bronze. He’s a hereditary member of the bronze casters’ guild too. But even though Kelly grew up learning traditional casting, his latest work is something new. After watching the men in his family melt down plumbing fixtures and cymbals, Kelly started scouring local garages for used spark plugs. During the pandemic he began shaping life-size sculptures using a welding torch. “The essence is upcycling—using the same objects for a different purpose,” he says.

Kelly’s work has been displayed in New York, London, and Lagos. But he’s never left Nigeria, never had the opportunity to see the ancient bronzes up close. For him, their return represents an inspiration to create art that mixes old and new. “We only see them online, on Google. Not everyone has access to the British Museum,” he says. “For people like me, it will change what’s possible.”

A few months later, at a gallery tour of the Humboldt Forum in Berlin, I’m surprised to see a familiar face sitting one row in front of me. It’s Phil Omodamwen. The Ethnological Museum, he tells me, acquired one of his latest works for its collection. He proudly points out the gleaming plaque hanging on a wall behind a display of historic bronze heads taken in the 1897 raid.

Just days before, he says, his long-held dream came true. Curators invited him to handle bronzes he had only seen in dog-eared catalogs. He was able to see the backs of plaques and chat with the museum’s restorer about his technique and how it compared with that of his forefathers. “When I saw those works, I was so happy,” he says, sighing. “Now I have a message of hope to take back to our people.”

This story appears in the March 2023 issue of National Geographic magazine.