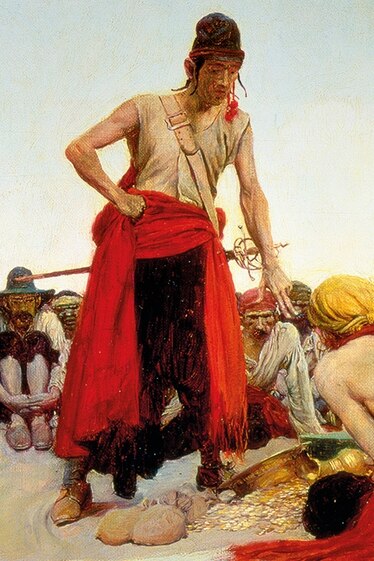

The 19th-century author Howard Pyle is responsible for a great many beliefs about 17th-century pirates, from their flamboyant costumes to their buried treasures. Published after his death, the 1921 Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates contains vivid illustrations alongside rollicking stories of life on the high seas. Historians have dismissed much of it as romanticized exaggeration, but his depiction of Port Royal still rings true:

[T]he town of Port Royal ... in the year 1665 ... came all the pirates and buccaneers ... and men shouted and swore and gambled, and poured out money like water, and then maybe wound up their merrymaking by dying of fever. ... Everywhere you might behold a multitude of painted women ... and pirates, gaudy with red scarfs and gold braid and all sorts of odds and ends of foolish finery, all fighting and gambling and bartering for that ill-gotten treasure of the be-robbed Spaniard.

The English captured Jamaica from the Spanish in 1655. They noticed the port’s strategic potential at the entrance to Kingston Harbour and set about strengthening its defenses. Bristling with fortifications, the harbor was expanded to accommodate ships. Traders flocked to the protected haven. But in addition to legitimate trade, the port’s prosperity also derived from less salubrious endeavors: piracy.

(Queen Elizabeth I's favorite pirate was an English hero and a Spanish villain.)

During the mid-17th century, England and Spain fought a primarily naval war that frequently targeted the others’ shipping lanes. The plan was simple: The English crown gave license for pirates to attack Spanish shipments on sea and on land. Pirates became known as buccaneers, or the more dignified-sounding privateers, in a form of state-sanctioned piracy.

Port Royal’s position at the heart of the Caribbean surrounded by the Spanish Main put it in striking distance of the main shipping routes between the New World and Europe, making it the buccaneering capital of the world.

Welsh pirate Henry Morgan used the town as his base and launched his attacks against Spanish cities, including Puerto Principe (today called Camagüey, Cuba), Porto Bello (Portobelo in Panama), Maracaibo (in modern Venezuela), and Panama City. His successful campaigns against the Spanish earned him a knighthood and political power in Jamaica where he served as governor and lieutenant governor. Morgan would die a rich man in 1688; his body was interred in a lead coffin in the Palisadoes cemetery in Jamaica.

Prisoners of Port Royal

Port Royal’s attitudes toward piracy shifted with the political tides. When England and Spain were at odds, piracy was lauded, but crackdowns did occur. During one such time in the 1670s (somewhat hypocritically supported by Henry Morgan), those charged formally with piracy were executed on Gallows Point in Port Royal.

In the early 18th century, Jamaica's new governor Nicholas Lawes brought in the English Navy to hunt down pirates operating in Port Royal. Local support for piracy began to wane after the capture and execution of several notorious pirates and their crews, including Calico Jack Rackham, Anne Bonny, Mary Read, and Charles Vane.

Rackham, Bonny, and Read were captured in 1720. Rackham and male members of his crew were executed at Gallows Point, but the women’s lives were spared because both were pregnant. Read died in prison (some say during childbirth), but Bonny’s ultimate fate is unknown.

After his conviction, Vane was hanged in 1721. To deter pirates, both the corpses of Rackham and Vane were publicly displayed—hung from gibbets near the entrance to Port Royal Harbour—as a warning to passersby and locals about what kind of fate awaited pirate captains and crews who got caught.

(Forget "walking the plank." Pirate portrayals are more fantasy than fact.)

Judgment day

The wealth accrued from legitimate trade and by pirates like Morgan turned Port Royal into one of the richest ports in the Caribbean, with brick houses of two to four stories, piped water—and innumerable brothels, gambling dens, and taverns. The Catholic Church condemned it as the “wickedest town in Christendom” for its state-sanctioned pirates and tolerance of human vice.

(Read an excerpt from a pirate's pilfered atlas.)

On the morning of June 7, 1692, the church rector of Port Royal, Jamaica, was running late for a lunch appointment, but a friend entreated him to delay just a while longer. It was a small choice that saved his life. The ground began to roll and rumble, but the friend waved off the rector’s alarm; earthquakes on the island usually passed quickly. But this quaking only increased in intensity, and the two men soon heard the church tower collapse into rubble.

The rector sprinted outside, racing for open ground. By his description, the land split open, swallowing crowds of people and homes in one gulp and then sealing closed. The sky darkened to red, mountains crumbled in the distance, and geysers of water exploded from the seams ripped in the earth. He turned to see a great wall of seawater swelling high above the town. In a letter describing the disaster, the shocked rector wrote, “In the space of three minutes ... Port Royal, the fairest town of all the English plantations, the best emporium and mart of this part of the world, exceeding in its riches, plentiful of all good things, was shaken and shattered to pieces.”

A tsunami followed the earthquake, which scientists believe measured 7.5 on the Richter scale, making it a “major” event. By the time the catastrophe had ended, most of Port Royal, including the cemetery where Henry Morgan was buried, lay beneath the watery depths. As many as 2,000 people were killed immediately, and thousands more died soon after.

Due to its licentious reputation, Port Royal faced what to many people must have looked like Judgment Day. It certainly felt that way to the church rector. In letters he confessed that he longed to escape the scene of the disaster but his conscience drove him to stay, venturing into the town day after day to pray with survivors in a tent pitched amid their flattened houses, which were looted nightly by “lewd rogues.” “I hope by this terrible judgment, God will make them reform their lives, for there was not a more ungodly people on the face of the earth,” he wrote.

(Who were the Maroons, Jamaica's freedom fighters? )

Submerged site

Covered by silt and 20 to 40 feet of murky water, the sunken town remained untouched for nearly 300 years until marine archaeologists began to bring artifacts to the surface. These discoveries have helped reveal the truth behind the dastardly legends.

One of the first explorations of Port Royal took place in 1956 when amateur archaeologist Edwin Link and his wife and research partner, Marion, visited the location. They pulled up a cannon from the fort but concluded that more specialized equipment would be needed to plumb the muddy bottom and the artifacts within it. They returned in 1959 with the Sea Diver, an innovative vessel that Edwin had designed himself for underwater exploration.

Over the course of a 10-week expedition sponsored by the National Geographic Society, the Smithsonian Institution, and the government of Jamaica, the Links’ crew, along with elite U.S. Navy divers, recovered hundreds of relics. By applying high-pressure water jets against the bricks, then sucking up debris and silt with an airlift, the salvors uncovered walls of brick and mortar. Once uncovered, breakable objects were brought to the surface by hand.

In the harbor’s clouded waters, visibility was limited for divers, who could barely see a hand held before their faces. They often resorted to working by touch alone, groping in the ooze.

One diver explained his experience of working blind: “I guess you develop a sixth sense once you have been down there awhile ... You get so engrossed in what you may find there that you forget everything else. You lose sense of time. You even forget to wonder if there are sharks near you.”But the dangers were very real. Sea urchins, stingrays, moray eels, and scorpionfish lurked, mostly unseen, on the muddy bottom. There was also constant danger of cave-ins as a dredge sucked at the base of old brick walls.

What the team found in the sunken pirate capital was akin to an underwater Pompeii. Marion Clayton Link described what originally attracted her and her husband to the site.“Unlike cities on land, which change with the years, this one remained exactly as it had been more than two and half centuries before—sealed by the seas in an instant earthquake. Whatever we might find in the ruins would be truly indicative of the time.” Researchers use the term “catastrophic sites” for such places where a sudden disaster has preserved important artifacts and the context of life around them.

From pewter tableware to Chinese porcelain, there were many signs of personal wealth. There were also numerous domestic objects denoting life in an ordinary household, such as spoons and lanterns, as well as elegant items like a wrought-iron swivel gun. A truly astonishing number of bottles and pipes were found, which gave the impression that people in old Port Royal did spend most of their time drinking and smoking. Edwin even inserted a hypodermic needle into the cork of a bottle and withdrew a sample of yellow fluid for a taste test. “Horrible. Tastes like strongly salted vinegar,” he sputtered. “I guess 1692 must have been a bad vintage year.”

The most fascinating discovery was probably an elegant brass watch. Manufactured in Amsterdam in 1686, it had stopped at what was considered the exact time of the earthquake: 17 minutes to noon.

These early explorations of Port Royal laid the foundation for more work. Starting in 1981, Texas A&M University led a 10-year excavation with the Institute of Nautical Archaeology and the Jamaica National Heritage Trust. Because of the oxygen-depleted environment under the water, the team recovered many organic artifacts that might have otherwise deteriorated. These finds have created an even more vibrant picture of what life was like in the Caribbean’s most notorious pirate port in the 17th century.

(Why there’s more to shipwrecks than just sunken treasure.)

Portions of this article appear in Lost Cities, Ancient Tombs, edited by Ann R. Williams. Copyright © 2021 by National Geographic Partners. Reprinted by permission of National Geographic Partners.