Nine days after the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, after his mother and year-old brother died and his home was incinerated, seven-year-old Masaaki Tanabe watched his father slip away. His last words: “I see no future as an army officer.” An implacable enemy of America, Tanabe’s father died with his sword at his side. Tanabe’s grandfather wanted to keep his son’s sword, but the occupation forces came and wrested it from him. “Barbarians,” young Tanabe thought. He was determined to take revenge against America, he says.

Understandable. He had nothing and almost no one left. His home had been next to Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, the now iconic building with the skeletal dome, preserved as an appeal for nuclear forbearance.

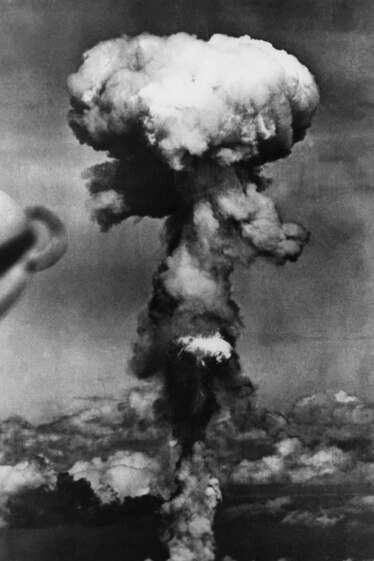

Now in his early 80s, Tanabe is a handsome man, square jawed and silver browed. He is tradition personified in his gray jinbei robe with wide sleeves. He’s also resourceful and adaptive. He became a filmmaker and studied computer graphics so he could construct a cyber version of the city that the bomb had erased. The result: Message From Hiroshima, a film that includes interviews with survivors of the August 6, 1945, bombing that—along with the atomic bombing of Nagasaki three days later—would kill up to 200,000 people, force Japan’s surrender in World War II, and render unnecessary an Allied invasion of Japan that could have killed millions.

Tanabe couldn’t have predicted the wrenching changes that awaited him and Japan. His daughter married an American and settled in the United States. Tanabe long wrestled with the idea that she had embraced the enemy. Two or three years after the wedding, Tanabe discovered a letter his daughter had left at the base of a stone Buddha in Yamaguchi Prefecture, where her grandfather—Tanabe’s father—had died. In it she told her grandfather she was sorry if she had disappointed him. As the years passed, Tanabe, like much of his generation, reconciled himself to a changed world.

Seventy-five years after the war’s end, Tanabe’s story is the story of Hiroshima, and of Japan itself: a mix of tradition and modernity, of a determination never to forget but also a commitment not to be defined solely by the past. And as with Tanabe, events personal and public have yoked the two former enemies, Japan and America, to a shared future.

Each August 6, the city pays homage to its 135,000-plus A-bomb victims, adding more names to a cenotaph. All other days of the year, its focus is decidedly forward. Today Hiroshima has a near-messianic zeal as the world’s champion of denuclearization, but it’s also a vibrant hub for recreation, research, and commerce.

After the bomb fell, Hiroshima was full of miraculous accounts of services restored—water, electricity, streetcars—and of unheralded heroes from near and far who helped bring the city back to life in the years afterward.

Nanao Kamada grew up in the countryside nearly 400 miles from Hiroshima. Until 1955, when he was applying to medical school in the city, he hadn’t thought much about the atomic bomb. But in Hiroshima he saw people wearing caps and long sleeves in searing heat, to conceal their burns. He would become an authority on treating A-bomb survivors and on radiation research.

Today Hiroshima’s problems are those of many Japanese cities—a declining birth rate, an aging population, inadequate hotel capacity for its more than two million yearly visitors, and aging buildings and infrastructure. But there’s a sense of urgency about preserving the memories of the survivors—the hibakusha. There are about 47,000 of them in Hiroshima; their average age is 82. The city has dispatched hibakusha around the world, in person and via the internet, to tell their stories. The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum has a video library of more than 1,500 survivors’ tales, some 400 viewable online. Some survivors are even available for video conferencing. Many say that sharing their stories gives more meaning to what they endured.

For some survivors, the unfounded fears of other Japanese citizens became more of a burden than the aftereffects of radiation.

Shoso Kawamoto was 11 when the bomb fell. He lost his parents, two sisters, and a brother. His surviving sister died of leukemia at 17. Though orphaned, he was fortunate: Rikiso Kawanaka, the owner of a soy sauce business in Tomo, a village some seven miles from Hiroshima, took him in.

Kawanaka fed and clothed Kawamoto. He also made him an unusual offer: If the boy agreed to work for 12 years without a salary, Kawanaka would give him a house. Years passed. Kawamoto rose at two in the morning and worked until four in the afternoon—all without pay.

When Kawamoto turned 20, he met a woman named Motoko. She was pretty and easy to talk to. She was learning to make dresses and kimonos. They fell in love.

When Kawamoto turned 23, Kawanaka made good on his pledge: He gave Kawamoto the promised house. With his own home, Kawamoto felt ready to ask Motoko’s father for permission to marry his daughter. But the father knew Kawamoto was from Hiroshima. He told him that any children the marriage might produce could be deformed from radiation (actually, no health effects have been found in children of Hiroshima survivors). He forbade the union.

Kawamoto was shattered. Two days later, with marriage denied him—as it has been for many hibakusha—he quit his job, walked away from the house for which he had sacrificed so much, and left his village. He never saw Motoko again and never again allowed himself to love, fearing more heartache. His life spiraled downward. He says he gambled and fell in with gangsters—yakuza. He considered suicide.

Eventually he found work in a noodle shop, his opportunities limited by his sixth-grade education and his status as a hibakusha, a modern-day leper to some. At 70, he returned to Hiroshima and there, finally, found some peace. Now 86, he’s a grandfatherly figure in a straw hat and cotton vest, seen reaching into a shopping bag and pulling out origami planes and cranes. He gives them to children who visit the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. Pull the tail, he says, beaming, and see the wings flap. Printed on the planes’ wings are the words “Hope for Peace.”

There is no undoing the discrimination Kawamoto and other survivors suffered. But at Hiroshima University’s Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine, director Satoshi Tashiro is determined to try to avoid such future discrimination. The institute aims to improve communication between the media and scientists, so that the public is not swayed by unwarranted fears. What happened to the hibakusha, he says, also happens to those who lived near Ukraine’s Chernobyl nuclear plant and Japan’s failed Fukushima reactor.

The Funairi Mutsumien Nursing Home houses some hundred bomb survivors. The youngest, now 74, was in utero at the time of the blast. The oldest is Tsurue Amenomori; she’s 103. When the bomb went off, she was less than a mile from ground zero, giving her bedridden parents medicine. She suffered burns on her face, hand, and leg. Today she is cheerful and prides herself on bounding up the nursing home’s stairs. She’s a favorite of the staff.

These survivors’ care falls to the Atomic Bomb Survivors Support Division, which has a staff of 32 led by Takeshi Yahata, a son of hibakusha. His grandfather disposed of corpses after the bombing; now Yahata’s division helps living survivors—with health care, social services, counseling, and nursing home and funeral expenses.

Even now, telling Hiroshima’s story can be contentious. A new exhibit at the peace memorial museum took 16 years to complete, partly because of disputes among the exhibition committee, says Shuichi Kato, the museum’s deputy director. Some members wanted stark pictures of the horrors of nuclear war; others argued for more restraint, afraid of traumatizing visitors. (During a recent visit I saw two people collapse.)

One debate was over what photo should greet visitors to the museum. It was resolved after Tetsunobu Fujii, the son of a survivor, saw a website photo of a young girl, her hand bandaged, her face bloodied and bruised. He believed it was his mother, Yukiko Fujii. The museum confirmed it was her, at age 10. The committee unanimously chose the photo for the exhibit’s entrance. Her photo at age 20 is at the exit. (She would die at 42.) They are iconic images, impossible to forget.

For many who survived the blast, survivor’s guilt and psychological scars endured. Emiko Okada, 82, wears a crane medallion around her neck, symbolizing hope and peace. She was eight when the bomb fell. That morning her 12-year-old sister, Mieko Nakasako, announced she was going out. She was headed to within half a mile of ground zero. I ask Okada whether her sister died in the blast.

“My elder sister is missing,” she says.

“Missing?” I repeat, wondering what that means after 75 years.

“She has not returned home yet.” There is something eerie about the word “yet,” as if Okada half-expects Nakasako to suddenly appear at the door. That lack of resolution haunts Okada.

Okada was not orphaned, but she may as well have been. Her parents desperately searched for their oldest daughter, abandoning Okada, who found herself living on the streets, sleeping in an air-raid shelter, eating what she could find or steal—a discarded tomato, a fallen fig. Only later did her grandmother take her in.

“My parents lost their minds after the loss of their daughter,” Okada says. When her mother was cremated, she adds, pieces of glass that had flown like projectiles that August day reappeared among her ashes and bone fragments.

For Okada and others, the horrors replay themselves even today. Okada hates evening glows, “like the sunset when the sky is orange or when the sky is really red, because that reminds me of the night of August 6.”

In Hiroshima the young come to terms with the city’s past in their own ways. Kanade Nakahara, 18, studied the bombing in school and in March 2019 went to Pearl Harbor on a field trip. She is determined to work for peace.

Others can’t relate to that distant period. Near the Bank of Japan, which survived the blast but was where 42 people were killed, I find 17-year-old Kenta, an avid computer gamer. He regards that day as “ancient history” and isn’t sure what year the bomb fell. He guesses 1964.

On the other hand, Haruna Kikuno, 18, shudders at the sound of passing planes—the result, she says, of reading books about the bomb as a child.

On the flight from Hiroshima to Tokyo, I introduce myself to the Hiyama family. Theirs too is the story of Hiroshima and its implausible history. The father, 44-year-old Akihiro Hiyama—“Aki”—grew up in Hiroshima, in a family of prominent political figures. His grandfather Sodeshirou Hiyama is honored with a statue for his contributions to Hiroshima’s rebirth.

Hiyama’s maternal grandmother, Keiko Ochiai, told him that a friend of hers had planned to travel the day Hiroshima was bombed, but fell ill. Rather than see her train ticket go to waste, she gave it to Ochiai. Soon after the train departed, Ochiai looked out the window and saw the mushroom cloud. Her friend did not survive.

Today Ochiai is 91. She married and had a daughter and grandchildren. Grandson Hiyama now lives in the U.S.—in Norfolk, Virginia. There, in 2005, he met Leah Shimer. They married and have two children: son Kai, seven, and daughter Emi, five, who hugs her stuffed unicorn.

During the war, Shimer’s grandfather Sterling Arthur Shimer helped design the engines of the B-29 Superfortress bombers. It was B-29s that rained tens of thousands of tons of explosives down on Japan, as well as incendiary bombs, and ultimately, the atomic bomb that decimated Hiroshima.

Between flights, Hiyama, Shimer, and I speak of those war years. Kai listens, trying to make sense of it all. “Mama,” he asks, “what’s a mushroom clown?” It falls to Shimer to answer. “Dust and debris went up into the sky when the bomb went off,” she tells him. “It was something really sad. A lot of people died.”

“They are sweet, innocent ears,” she says later. “I am glad I can be the one to introduce some of this to him.” But Kai has one more question: “Are America and Japan still enemies?”

“No,” his mother says, “they are friends.” And with that, the family heads for its gate and the long flight home.