The 17th-century French historian, François Eudes de Mézeray, chronicled a plague that swept through southern France in the 10th century: “The afflicted thronged to the churches and invoked the saints. The cries of those in pain and the shedding of burned-up limbs alike excited pity; the stench of rotten flesh was unbearable.” Throughout the Middle Ages, many outbreaks occurred, some taking tens of thousands of lives. Symptoms included convulsions, hallucinations, and excruciating burning sensations in the limbs. Dubbed ignis sacer, holy fire, the affliction blackened the limbs until they fell off at the joint.

Common wisdom of the time held that the sickness was spiritual and that divine intervention could treat it. Special hospitals were set up, manned by monks of St. Anthony of Egypt, famous for his spiritual strength in the face of torment from the devil. The terrible condition was then associated with the saint, and became known as St. Anthony’s fire. (See also: The science behind the Plague.)

The Saint and his sufferers

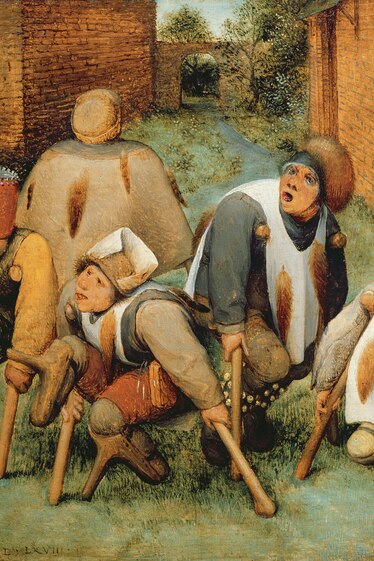

The monastic members of the Hospital Brothers of St. Anthony would have been a familiar sight in medieval Europe. Many wore on their habit the T-shaped St. Anthony’s cross—also called a tau cross, for its similarity to the Greek letter of that name. Of the 370 or so hospitals built and run by the order across Europe, the most celebrated is that of Isenheim, near Colmar in northern France. Here, in homage to the hermit saint whose relics were said to cure sufferers of St. Anthony’s fire, the monks commissioned a great altarpiece for the monastery hospital’s chapel in the early 1500s. Sculpted by Niclaus of Haguenau and painted by Matthias Grünewald, the masterpiece is today housed in the Unterlinden Museum in nearby Colmar. A panel shows the saint learning humility from an older hermit monk (right). In the left panel, the saint is assailed by hellish creatures who test his resolve to stay true to Christ. A tormented figure in medieval garb (lower left) may bear symptoms of ergotism—a reminder that faith could deliver Isenheim’s patients from their physical anguish, as their saint had been delivered from his spiritual suffering.

Fire Starter

In the 18th and 19th centuries science revealed that the condition is caused by eating grain infected with a fungus, Claviceps purpurea. Infected plants bear black growths resembling a rooster’s spurs (ergot in French), giving the condition its modern name: ergotism.

When ingested, ergot produces toxic alkaloids that cut off the blood supply to the body’s extremities, turning the limbs gangrenous and creating the hellish sights described by Mézeray. Symptoms emerged when people ate the grain or any foodstuffs made from it. Cows are also affected by ergot. Accounts describe how their hooves and tails turned gangrenous, milk production stopped, and death typically followed. Outbreaks of St. Anthony’s fire caused widespread devastation to rural communities.

There is evidence that ancient people were aware of the condition’s association with grain. An Assyrian tablet from the seventh century B.C. refers to pustules on an ear of grain, while holy Zoroastrian texts in Persia refer to grasses that caused pregnant women to miscarry or die in childbirth, another of the poison’s dreaded effects.

In medieval Europe increased rye cultivation and consumption, mostly by the poor, exposed large parts of the population to the risk of contracting St. Anthony’s fire. Ergotism did not affect all of Europe in equal measure. It is now known that Claviceps purpurea spores proliferate where there is cool, damp weather when grain ripens, conditions particularly prevalent in large areas of central Europe.

In the ninth century a devastating outbreak of gangrenous ergotism killed tens of thousands in the Rhine Valley. The physical burning sensation sufferers felt in their limbs linked the disease to hellfire, giving the sense that the illness had been sent down as a divine punishment.

Faith Healing

Religion became an important factor in dealing with the disease. In 1070 relics of St. Anthony of Egypt were brought from Constantinople to a small town in southeastern France, where they were looked after by Benedictine monks. Soon, the relics became associated with a miraculous cure for ergotism, marking the moment when the condition first became called St. Anthony’s fire. (See also: Unlocking the healing power of belief.)

St. Anthony, also known as St. Anthony the Great, was a religious hermit of the third and fourth centuries A.D., credited with inspiring Christian monasticism in Egypt. According to his biographer, he began practicing asceticism as a young man and retreated to live alone on a mountain for roughly 20 years. During this time, Christian tradition holds that the devil presented Anthony with a series of temptations—some carnal, others seductive, and some horrifying—but Anthony’s faith granted him the strength to resist them all.

In the 11th century Guérin la Valloire, a young French nobleman, was suffering from St. Anthony’s fire. He recovered from the dreaded affliction and credited his renewed health to the saint’s relics; he and his father founded what would become the monastic order of the Hospital Brothers of St. Anthony around 1095. The condition’s association with St. Anthony was further strengthened because the vivid hallucinations induced by ergot poisoning were linked to the visions shown to Anthony by the devil.

By the end of the 15th century the monks had built roughly 370 hospitals across Europe, with locations in France, Flanders, Germany, Spain, and Italy to treat outbreaks of St. Anthony’s fire. The brothers were also instrumental in caring for those infected with the Black Death in the 1300s. In France the hospitals were known as hôpitaux des démembrés, hospitals of the dismembered, reflecting the custom whereby sufferers would display their amputated limbs at the entrance, as offerings. The disease particularly affected the poor, who ate substantial amounts of inexpensive rye bread. The relative success of these well-endowed hospitals may be attributed to feeding their patients bread made from uninfected grains, like wheat or other cereals.

The monks also applied a topical, lard-based ointment called St. Anthony’s water to affected areas. This treatment was often imbued with medicinal plants, like different varieties of nightshade. They also prescribed drinking St. Anthony’s wine. Considered a powerful antidote to the disease, it was made from grapes at the abbey near Vienne in France where the saint’s relics were housed. Their presence was believed to infuse the miraculous vintage with healing properties.

The Fire Dies Down

Outbreaks of similar conditions were often attributed to ergotism. In Germany, Italy, and Flanders in the 15th and 16th centuries, whole populations started to dance uncontrollably. Called St. John’s dance, St. Vitus’ dance, and tarantism, the condition, like St. Anthony’s fire, was associated with demons and devils. One modern theorylinks the dance mania to rye poisoning as well. But this notion is problematic, in part because it occurred in communities where rye was—and was not—eaten. Ergotism is also thought to be a cause of the witchcraft scares, particularly in the 17th-century Salem Witch Hunt in colonial Massachusetts, although this theory has been challenged as well. Curiously, as North America was persecuting witches, a French physician, Thuillier, definitively linked rye ergot fungus with the condition in 1670.

Outbreaks of St. Anthony’s fire began to die down as wheat replaced rye and became more widespread throughout the 1800s; however, ergotism didn’t disappear completely. Almost 12,000 people were infected in 1926 in the Soviet Union, and Ethiopia and India experienced outbreaks in the late 20th century.