Childhood education in ancient Greece was highly dependent on one’s gender. Preparing for life in the public sphere, wealthy boys during the classical period went to schools where they faced both physical and mental challenges. Relegated to the private sphere, girls’ educations were typically haphazard, often occurring at home, if they occurred at all.

In the fifth century B.C., Greece’s greatest minds were preoccupied with the most effective ways to raise children. Isocrates, a Greek rhetorician and contemporary of Plato, boldly proclaimed what he saw as Greece’s leadership in education: “So far has Athens left the rest of mankind behind in thought and expression that her pupils have become the teachers of the world.” (See also: Wine, women, and wisdom: The symposia of ancient Greece.)

The teaching that Isocrates praised was known by Greeks as paideia, a term derived from pais, the Greek word for child. In ideal terms, paideia was intended to allow male children to purge the baser parts of human nature so they could achieve the highest moral state. On a pragmatic level, it also provided society with well-prepared men to take on the political and military burdens of citizenship as adults.

Paideia, however, was not intended for female children. Generally, only wealthy families could afford the full range of educational opportunities, and in nearly all cases, those children were boys. Most daughters, even well-off ones, received an informal education at home. In classical Greece, women were not educated for service in public life, as only men could be citizens. Although evidence has come down of some important exceptions, in general the role in life allotted to girls was in the home. (See also: Once sacred, the Oracle at Delphi was lost for a millennium. See how it was found.)

From heroes to thinkers

The notion of paideia did not suddenly emerge in the time of Isocrates, but developed slowly over time. Child-rearing customs that developed in Greece’s Archaic period, from the eighth century B.C. onward, were restricted to a tiny elite of young male aristocrats. They centered on rules and moral dictums—the respect that one owed to parents, the gods, and strangers, for example.

As the literature of Homer spread through the Greek world, the heroes of the Odyssey and the Iliad were held up as examples to inspire young men. A prized quality in the Homeric hero was arete, a blend of military skill and moral integrity.

With the Homeric foundation, scholars began to develop more complex ideas around education. In the fifth century B.C., around the time of Socrates, a new kind of professional teacher, the Sophist, became popular in Athens. Teaching their students rhetoric and philosophy, Sophists infused the traditional values of arete with a new spirit of intellectual inquiry. It is during this period that the word paideia is first found. The movement advocated higher education for young Athenian men starting around the age of 16.

There were notable exceptions to this new emphasis on the life of the mind. In neighboring Sparta, harsh child-rearing customs placed an almost exclusive emphasis on physical prowess to prepare for a soldier’s life. Even so, the development of paideia was not restricted to Athens, and formed part of a pan-Greek culture. (See also: Ancient Spartans were bred for battle.)

Sport

From cradle to school

Children of wealthy Athenians in the later fifth century B.C. would typically spend their early years at home. Daughters and sons were raised under the care of female relatives, slaves, and perhaps grandparents. Segregation would come later.

The head of the family was the father, who was not expected to play a big role in domestic life, but rather to be concerned with public or military affairs. If the father brought male friends to his home, they would assemble in the andron, the part of the house set aside for male get-togethers.

At the age of six or seven, boys would leave home for the schoolroom. Even though education was almost exclusively focused on the forming of citizens, Athenian schooling was not funded or organized by the public. Families were responsible for their sons’ educations.

One of the two figures of authority in a young schoolchild’s life was the paidagogos, an older man, often a trusted family slave, who would accompany the boy to school. He was responsible for ensuring the boy’s well-being and teaching him good manners: Walking properly along the street with lowered eyes, wearing his cloak correctly, sitting properly, remaining silent, and not being greedy. To enforce such manners, he could employ corporal punishment.

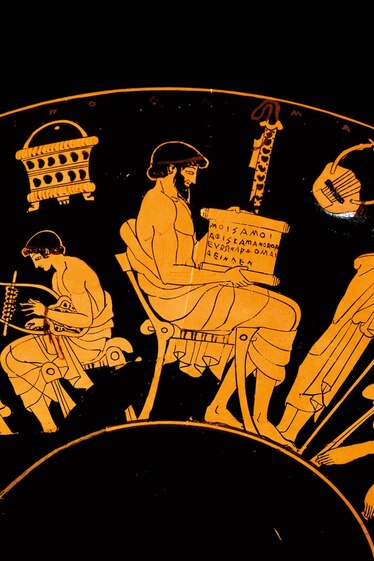

The second figure was the schoolmaster himself, of which there were three types: grammatistes, who taught grammar; kitharistes, who taught music; and paidotribes, who taught physical education.

Becoming Human

If Greek education centered on refining the baser elements of human nature, babyhood was a process of becoming human in the first place: “They are born in a more imperfected condition than any other animal,“ Aristotle wrote of newborns, noting that babies cannot even nurse with their heads unsupported. As well as weakness, Greek infants were associated with an animal wildness that needed to be tamed: Aristotle likened a crawling baby to a four-footed animal. Infanticide was not uncommon in Athens. Babies (especially girls) were left to die if they were seen as an unwanted financial burden.

“To rear children is a hazardous undertaking and success is won through struggle,” wrote the fifth-century B.C. thinker Democritus. Other sources take a more joyful view. In Euripides’ play Ion, for example, children are lauded for lighting up the “old dark house” of life.

In reality, these subject areas are wider in scope than their English translations suggest. “Grammar” consisted of arithmetic, literature, and ethics. “Music” centered on the playing of instruments such as the lyre and pipes. Reflecting the wider sense of the word “music,” related to the Muses, it was also a vehicle for imparting broader knowledge about history and ethics. Physical games included gymnastics and field sports. Wrestling contests were held in the building known as the Palaestra.

Basic education for boys ended between the ages of 14 and 16. By 480 B.C., Athenians had the option of enrolling their sons in secondary schooling. For older students rhetoric was a central area of study, especially for those eyeing a career in public life. Those who could afford it also took private lessons from the Sophists, who were far more expensive than conventional teachers.

Intense relationships between an adult male teacher and an adolescent pupil could often develop. At times such relationships could turn sexual. Although such interactions were socially accepted, the practice was officially frowned on in Athenian democracy.

Most wealthy Athenians’ education terminated with an obligatory period of military service, which began when a young man entered the ephebos social class at age 18. In the fourth century B.C., the intellectual elite might hope to go on to study at one of the new centers of philosophy: the Academy, established by Plato circa 387 B.C. , and the school established at the Lyceum by Aristotle around 335 B.C.

At School

Female education

In stark contrast to the traditional, family-centered childhood of Athens was Sparta’s rigid schooling system. Known as agoge, it was centrally organized by the state. From the age of seven, boys were given a military education more focused on survival. They were beaten, taught to steal, and learned to withstand cold and hunger.

Whereas Athenian education imposed a strict segregation of the sexes, Spartan boys and girls trained and competed in athletics alongside one another. The first-century Greco-Roman writer Plutarch described how Spartan girls were required to “exercise themselves with wrestling, running, throwing the quoit, and casting the dart, to the end that the fruit they conceived might, in strong and healthy bodies, take firmer root and find better growth.”

Although it is broadly accepted that girls in Athens and other parts of the Greek world were denied access to the teachings offered to boys, it does not mean they received no education at all. Historians believe girls were taught literature and math, as well as dancing and gymnastics. Even so, a lack of documentation on women’s lives in a classical Greece makes it hard to assess what kind of educational experience many had. Some artworks depict female students: a fifth-century B.C. kylix depicts one carrying a tablet and stylus. Another shows a girl reading from a papyrus.

Some women found ways to excel. The great lyric poet Sappho, active on the island of Lesbos in the seventh to sixth centuries B.C., composed about 10,000 lines, 600 of which have survived. The young women who surrounded her have sometimes been understood as her pupils, as if she were a formal teacher. It is more likely, however, that the group was a literary coterie rather than a formal school.

Going global

Many of the principles of paideia have been handed down through time and incorporated into learning institutions, a process that was largely enabled by the spread of Christianity. The fifth-century Christian thinker St. Augustine argued for the continued study of classical texts and the importance of rhetoric in education.

Augustine believed eloquence and argument could help win souls for the church. His inclusive approach shaped medieval and Renaissance learning, which in turn has hugely influenced modern ideas about education. Despite the gulf of time and values that separate the world of classical Athens from schools in the 21st century, these debates still influence the way people think about education in the United States, Europe, and many other parts of the world today.