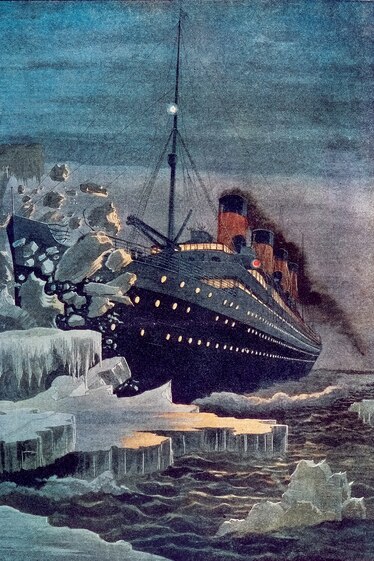

Three days after the Titanic set sail from Southampton, England, on its maiden voyage, Captain Edward J. Smith followed a normal Sunday routine. He inspected the ship but declined to conduct a scheduled safety drill. He led a worship service and then met with his officers to fix the ship’s position. According to their calculations, the Titanic averaged a sprightly 22 knots. As the sun set on April 14, 1912, the temperature lowered to freezing. The sea’s surface shone like glass, making it hard to spot icebergs, common to the North Atlantic in spring.

Nevertheless, Captain Smith kept the ship at full speed. He believed the crew could react in time if any were sighted.

First warnings

Icebergs did indeed lay ahead. By 7:30 p.m., the Titanic had received five warnings from nearby ships. Marconi wireless operator Jack Phillips took down a detailed ship’s message pinpointing the location of “heavy pack ice and a great number of bergs,” but Phillips, busy sending passengers’ personal messages, apparently did not show it to any officer.

At 10:55 p.m., another ship, the Californian, radioed to say it had come to a full stop amid dense field ice. Neither of these messages began with the crucial code that would have required Phillips to show it to Captain Smith, and Phillips was not in the mood for interruptions. The Californian’s electric signal was so close it nearly deafened Phillips. “Shut up, shut up!” he radioed back. “I am busy!” A while later, the Californian’s radio operator shut down for the night.

As the Titanic surged onward, lookouts Frederick Fleet and Reginald Lee peered into the darkness. Just before 11:40, Fleet noticed something blacker than sea lying directly ahead. As the ship drew closer, recognition dawned. He rang a warning bell three times and phoned the bridge.

“What did you see?” came the voice through the receiver. “Iceberg, right ahead,” replied Fleet.

Failed attempts

On the bridge, First Officer William Murdoch yanked the handle of the engine room telegraph to “stop” and barked an order to steer left. Murdoch also ordered “full speed astern” to try to avoid the ice. Then he pushed a button to close doors in the watertight bulkheads.

For more than 30 seconds, they held their breath. At the last moment, the Titanic’s bow swung to port and the mountain of ice slid along the starboard side. Fleet figured the ship had escaped.

But there’s more to an iceberg than meets the eye—nine-tenths of a berg is hidden below the surface—and its underwater bulk punched Titanic’s starboard hull plates. Many passengers didn’t notice the impact, but those in the bow knew they had bumped an iceberg because chunks fell in the well deck.

Below, in the forward boilers and mail rooms, the crew worried as water gushed into the first five compartments. The Titanic’s fate was clear. The “watertight” bulkheads would do no good. They rose only as high as E Deck—above the surface in a sound ship, but useless if the ship’s bow began to sink and seawater lapped the bulkheads’ top edges.

The weight of water entering the first five compartments would pull the ship deep enough to let more spill into the sixth, pulling the ship even deeper and then causing spillover into the seventh. Inevitably, each compartment would fill and flood the next. The crew estimated the Titanic had two hours or so to live.

‘Women and children, first’

Smith gave orders to send a radio call for help, fire the distress rockets, and fill the lifeboats.

A cruel snag of bureaucracy became evident. According to out-of-date yet still standard Board of Trade regulations, all ships exceeding 10,000 tons had to have at least 16 lifeboats plus additional rafts and floats. Those numbers worked fine for old-style passenger liners in 1896, the year of their adoption, but proved shamefully inadequate for behemoths such as the Titanic, which registered more than 46,000 tons. The Board of Trade also believed that stronger ships of recent construction likely could not sink, rendering moot the issue of lifeboat capacity.

The Titanic’s board-approved lifeboats, spread among 16 wooden craft and four canvas-sided Engelhardts, could seat only half the people aboard. Many would be have to be left behind.

The ship’s officers knew how many the lifeboats could seat, but they did not fill them to capacity for two reasons. First, Second Officer Charles Lightoller testified that the crew doubted the lowering mechanisms could bear the weight of 70 passengers per full boat. Second, crew members knew they could not waste time before launching; to do so would risk the ship sinking before all lifeboats and Engelhardts could be lowered to the sea. In fact, time ran out on the final two boats. One dropped into the sea before the crew could complete the launch, and waves swept another overboard, upside down.

All told, lifeboats left the Titanic with more than 400 empty seats. Relatively few occupants were men. When Smith ordered lifeboats filled, he hoisted a megaphone and barked, “Women and children first!” On the port side, Lightoller filled the boats with women and children only, except for one passenger with sailing experience. In contrast, First Officer Murdoch on the starboard side interpreted the order differently. He boarded as many women and children as were available, then gave remaining seats to men.

Why so few lifeboats?

The Titanic carried about 2,200 passengers on its maiden voyage, and the lifeboats and collapsibles had room for 1,178—more than the number required by British shipping regulations, which followed an outdated safety formula and only required lifeboat seats for 962. The Titanic’s only safety drill was rudimentary at best—two lifeboats lowered on sailing day, and passengers received no instruction on how to respond in an emergency.

Final moments

Water continued to flood the ship. Roughly two hours and forty minutes had passed since the iceberg struck the ship when the Titanic’s stern rose high out of the water and the bow plunged below. Passengers in lifeboats watched in horror as those still aboard scrambled up the sloping aft deck to gain a few final seconds before sliding or jumping into the ocean.

On April 15, 1912 at 2:20 a.m., the Titanic disappeared beneath the frigid waters. All who had failed to find a life-boat seat went into the frigid water. A life jacket did virtually no good. More than 1,500 people—ranging from the ultra-wealthy to the working class—drowned or died of hypothermia.

For those who made it to the lifeboats, help was on the way. While it was sinking, the Titanic managed to contact the R.M.S. Carpathia, which arrived around 4:00 a.m., to rescue the estimated 705 survivors of the Titanic.

Portions of “Why so few lifeboats?” appear in Return to Titanic by Robert D. Ballard, with Michael S. Sweeney. Copyright © 2004 Odyssey Enterprises, Inc. Text Copyright © 2004 National Geographic Society.