As an epic poem about the Trojan War, that momentous clash of two great armies around the city of Troy, Homer’s Iliad describes many acts of combat. Of these, the climactic battle to which all the epic action has been driving is the ferocious duel between the Greek Achilles and the Trojan Hector.

Despite their very different personalities, the two men share general traits. Both are noble; Achilles is the son of a goddess and the king of Thessaly. Hector is the son of the king and queen of Troy. Both are the outstanding warriors of their respective armies. Both men are young and honorable in their different ways, and both men, as the epic takes pains to show, want desperately to live.

For both, their final confrontation is highly personal. Achilles’ devastation of the Trojan army and its allies claimed the lives of Hector’s own brothers and brothers-in-law. Hector in his turn has slain Achilles’ closest comrade, Patroclus. And, improbably, the two heroes also briefly share a spectacular set of armor. How Hector came to wear it and the consequences of his doing so, accounts for one of the most dramatic themes in the entire epic.

The cause of the Trojan War, famously, was the elopement of beautiful Helen, queen of the Greek city of Sparta, with Paris, Hector’s brother and a handsome prince from the Asiatic kingdom of Troy. While Helen and Paris are the catalysts for the action in The Iliad, their decision to marry is 10 long years behind them when the epic opens. The poem focuses on the tragic consequences of their rash act of passion, the war itself. Thus, The Iliad’s subjects are the relentless engagement of armies, of individual warriors locked in perpetual battle, of constant preparation for and recovery from combat, and the cost in human terms of this combat—the killing and the dying, and the rage and grief the deaths incur. (Here's how archaeologists found the lost city of Troy.)

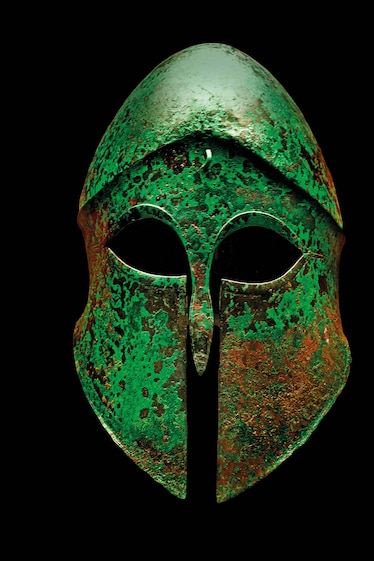

Arms and armor

By best estimate, The Iliad was composed around 750-700 B.C., but this final composition followed at least five centuries of oral storytelling by generations of poets before Homer. The epic tradition that culminated in the poem, then, had roots deep in the Bronze Age, so-called because societies at this time either made or traded objects made of the copper-tin alloy that constitutes bronze. This was a major technological advance that revolutionized the production of farming and work tools, household objects, jewelry, cult objects—and weapons of war.

Bronze is harder than copper, harder indeed than iron, and bronze-pointed spears set on wooden shafts, bronze-tipped arrows, and bronze slashing and thrusting swords were objects of enormous utility, prestige, and value. Similarly, bronze armor—helmets for the head, shields and breastplates for the body, greaves for the shins—were a warrior’s best chance of protection against the bronze-hard weapons he would encounter on the battlefield. (This 3,500-year-old bronze hand is Europe’s earliest metal body part.)

Given its subject, it is unsurprising that there are more detailed descriptions of armaments and weapons in The Iliad than of any other class of object. Of all the weapons described, nothing compares to the armor of Achilles, who possesses two sets of armor in the epic. Each one is peerless and corresponds with two distinct stages of his engagement with the war. First, as the Greeks’ most fearsomely effective combatant; second, when he withdraws from the fighting in a rage at his commander in chief Agamemnon, who confiscated his war prize, a woman named Briseïs, whom Achilles claims to love.

Born of the goddess Thetis and the mortal king Peleus, Achilles is a demigod, a cut above all the other heroes in whom no divine blood, or ichor, flows; and yet, like them, he is mortal. Nonetheless, his close relationship with the Olympian gods brings him advantages. His mother has direct access to Zeus, the king of the gods, and can ask favors of him for her son, bypassing the usual route of offering up prayers.

On the battlefield, Achilles is equipped like no other. His divine warhorses, a wedding gift from the god Poseidon to his father, were sired by the west wind. His trademark ash-wood spear, which no other hero is strong enough to wield, was a wedding gift to his father from the centaur Chiron. He possesses “stupendous armor, a wonder to behold, / a thing of beauty; the armor the gods gave to Peleus” (Il. 18.83-84), yet another wedding gift.

Most remarkable, it seems Achilles has a choice of fates, which is revealed when his comrades come to his quarters to beg him to return to battle. Achilles refuses, and in a momentous speech he declares that he knows he will lose his life if he returns:

For my mother tells me, the goddess Thetis

of the silver feet,

that two fates carry me to death’s end;

if I remain here to fight around the city of

the Trojans,

my return home is lost, but my glory will be

undying;

but if I go home to the beloved land of my father,

outstanding glory will be lost to me, but my

life will be long. (Il. 9.410-45)

Thus the armor that Peleus gave Achilles lies idle, and—because of his absence—the tide of battle turns against the Greeks, whom Homer calls Achaeans. At length, Patroclus makes a desperate, fatal request of Achilles—to borrow the distinctive armor “with the hope that likening myself to you the Trojans will hold off / from fighting, and the warrior sons of the Achaeans draw breath / in their extremity” (Il. 16.40-43). Reluctantly Achilles accedes to his dear friend’s plea. Wearing the trademark armor of Achilles, Patroclus sets forth to battle against Troy. (Homer's Iliad contains timeless lessons of war.)

Patroclus’s heroism results in the desired respite for the Achaeans—but also in his own death, which is greatly enabled by the god Apollo, an unyielding champion of the Trojans:

[C]loaked in thick mist Apollo met him,

then stood behind and struck the back and

broad shoulders of Patroclus

with the flat of his hand; so that his eyes spun.

From his head Phoebus Apollo struck the helmet;

and rolling beneath the horses’ hooves it rang

resounding,

four-horned, hollow-eyed, the horsehair

crest defiled

with blood and dust. Before this it was

forbidden that

the horsehair-crested helmet be defiled by

dust,

for it had protected the handsome head and

brow of the god-like man

Achilles; but now Zeus gave it to Hector

to wear on his head; but his own death was

very near.

In Patroclus’ hands the long-shadowed spear was wholly

shattered,

heavy, massive, powerful, pointed with bronze;

from his shoulders

his bordered shield and belt dropped to the

ground;

then lord Apollo, son of Zeus, undid his breastplate.

Confusion seized his wits, his shining limbs

were loosed beneath him,

Patroclus stood stunned. Behind him, in his

back, between his shoulders,

a Trojan man struck with a sharp spear

at close range (Il. 16.790-807)

Struck first by a god and then by a Trojan man, rendered utterly vulnerable, Patroclus attempts to retreat but is caught and slain by Hector, who vaunts over the dead man— and strips him of his armor. A bitter fight ensues between Achaeans and Trojans for this great prize, and at length the Trojans prevail. Hector is quick to exchange Achilles’ armor for his own—an act of hubris that causes Zeus, who is watching from the heights of Olympus, to shake his head in disapproval.

A new set of armor

Back at the Achaean camp, Achilles learns of Patroclus’s death. Instantly his anger with Agamemnon evaporates, and he is filled with sorrow for his fallen friend and rage at Hector. Bent on revenge, he declares he will return to the fighting and asks his goddess mother to obtain new armor. With this request, Achilles takes a decisive step on the path that leads inexorably to the fate he once sought to avoid—an early death.

Action on the field of war stops, and the epic follows his mother Thetis to the divine workshop of Hephaestus, master smith for the gods. In the bustling magical workshop, with its great bellows and ingenious mechanical attendants, Hephaestus forges Achilles’ brilliant new armor. (Meet 10 of the hardest working moms in history.)

With its creation, Achilles crosses a landmark line in his own life. The armor that his mother has entreated for his protection is in fact a token of his approaching death. All this is known to Hephaestus. He will create the most splendid armor any mortal man has ever worn, but, as he tells Achilles’ mother, it will not save her son’s life:

Would that I were so surely able to hide him

away from death and

its hard sorrow,

when dread fate comes upon him,

as he will have his splendid armor, such as

many a man

of the many men to come shall hold in wonder,

whoever sees it. (Il. 18.464-467)

Pouring all his skill into the work, Hephaestus creates a magnificent helmet, breastplate, and greaves, but his masterpiece is the shield:

[A]nd on it

he wrought with knowing genius many

intricate designs.

On it he formed the earth, and the heaven,

and the sea,

and the weariless sun and waxing moon,

and on it were all the wonders with which the

heaven is ringed (Il. 18.482-485)

On it too are depictions of cites and the life within them, weddings, counsels, shepherds with their flocks, farms, and vineyards. In short, the shield that Achilles will carry into war bears upon it all the variety of life he will shortly lose.

Stepping again onto the Trojan plain, Achilles cuts a blazing swath through the fighting, until fate brings him face to face with Hector, who is wearing the armor he stripped from Patroclus. As Hector watches Achilles approach, his courage breaks and he briefly contemplates putting aside his armor altogether and, naked as he would be, offering terms to Achilles, but this fantasy passes and goaded by Athena in disguise as his own brother, Hector stands to fight:

As a star moves among other stars in the

murky milk of night,

Hesperus the Evening Star, the most beautiful

star to stand in heaven,

so the light shone from the well-pointed

spearhead that Achilles

was shaking in his right hand, bent upon evil

for Hector,

surveying his handsome flesh, where it might

best give way. (Il. 22.306-321)

Scholars believe that in pre-Homeric tradition, Achilles’ trademark ash-wood spear had magic powers, such as never missing its mark, or returning to its owner after being thrown—yet in The Iliad it is merely a formidable weapon. Likewise, Achilles’ divine horses can run with the wind, but in The Iliad they cannot carry him from death. Similarly, there are clues that in pre-Homeric tradition the armor of Achilles was also once “magic,” making the hero who wore it invincible. This theory makes sense of the bizarre circumstances of Patroclus’s death. No other hero is struck by a god as Apollo strikes Patroclus, and his purpose in doing so seems to be not just to stun Patroclus, but to divest him of Achilles’ magic armor. (This author says "It's a mistake to think of Homer as a person.")

Now as Achilles and Hector face each other, all of Hector’s body is clad in this same armor, except “at the point where the collarbone holds the neck from the shoulders there showed / his gullet”(Il. 22.224-5). At precisely this point Achilles strikes, mortally wounding Hector. Is Achilles’ predatory eying of Hector’s flesh simply a function of his strategic skills as a warrior—or another remnant of an older version in which Hector wore his magic armor, and Achilles had to seek the only niche of vulnerability?

The final poet of The Iliad, inheriting an epic tradition that was at least half a millennium old, undoubtedly had at his disposal crowd-pleasing features such as magic horses, magic potions, caps of invisibility, and magic armor to protect his story’s favorite heroes. But Homer, it seems, aspired to something more profound. In his telling, even a demigod like Achilles is made of flesh that can be wounded and blood that can flow. The Iliad inherited from Homer has been honed to deny the audience any evasion of its message: War is a fearful business and not even heroes will escape unscathed.

A veteran contributor to National Geographic Caroline Alexander has written extensively on Homer, including a translation of The Illiad.